Last year's Christmas will be remembered not only for the gift I gave my father but also for the accounting I'd done of the season, and of holidays and memories past. I can't make fanfare of every year — nor should I, I suppose. Let the essay stand for a few years before recollecting traditions new and old again.

For the last eight years or so I've felt that a Christmas without good reading wrapped under the tree is one that runs a bit short. Thankfully, my family has obliged; this year, too. Two gifts I inspired, in spite of my withholding of a list: not long before this season, I was struck from nowhere with the desire for books on the English language. Etymology, puzzles; anything rigorous and interesting would do. It's a topic I've enjoyed for years but about which I know I can always learn more. I told my mother, who, I learned Christmas morning, contacted her librarian friend, the mother of my childhood pal. My mother explained; her friend made a short search and offered her a list of titles. A trip was made to Borders to find and buy a magnificent book called The Adventure of English, a colorful narrative of the language from its Saxon-borne Frisian roots to modern speech and writing. Surviving invasion and cultural contention, the language has found strength in adaptability, appropriating liberally from languages to become even more diverse and resilient.

Ironically enough, that librarian friend, who emigrated decades ago from India, recently remarked to my mother that she and her friends think in Hindi. English, she reminded my mother, is a difficult language to learn. My mother and I both nodded. We'd both taken French in school, a language which, once its distribution of articles and accents is understood, is structurally logical and pleasantly unsurprising. English is very unpredictable, no rule holding fast, from spelling to pronunciation to vocabulary. Conformity can't be had by a patchwork quilt. Ironically, Henry V's drive to reestablish English as the country's language of authority required scribes of Westminster to permanently define standard spellings and grammar, resulting in some arbitrary choices of English roots for some words, French or Norse or other languages for others. So nearly halfway through Adventure, author Melvyn Bragg gives us a spirited defense of English from the schoolroom:

We'll begin with the box and the plural is boxes

But the plural of ox should be oxen not oxes.

Then one fowl is goose, but two are called geese.

Yet the plural of a mouse should never be meese.

You may find a lone mouse or a whole ot of mice.

But the plural of house is houses not hice.

If the plural of man is always called men,

Why shouldn't the plural of pen be called pen?

...The masculine pronouns are he, his and him

But imagine the feminine she, shis and shim!

So our English, I think you'll agree

Is the trickiest language you ever did see.

A language perfectly tailored to, as Bragg puts it, "winnow out the undereducated, stump children and fox foreigners." At least English believes in intimacy: either you know her or you don't.

The title of this post, by the way, is a succession of Latinate French, Latin and Old English; all likely a part of the language by the beginning of the 17th Century. The Adventure of English wins my recommendation.

Today is the 231st anniversary of the Boston Tea Party:

The Boston Tea Party took place this day, December 16, 1773, just three years after the Boston Massacre, where the British fired into a crowd, killing five.The British passed unbearable taxes:

1764 Sugar Act -taxing sugar, coffee, wine;

1765 Stamp Act -taxing newspapers, contracts, letters, playing cards and all printed materials;

1767 Townshend Acts -taxing glass, paints, paper; and

1773 Tea Act.While American merchants paid taxes, British allowed the East India Tea Company to sell a half million pounds of tea in the Colonies with no taxes, giving them a monopoly by underselling American merchants.

Disguised as Mohawk Indians, a band of patriots called Sons of Liberty, led by Sam Adams, left the South Meeting House toward Griffin's Wharf, boarded the Dartmouth, Eleanor and Beaver, and threw 342 chests of tea into the harbor.The men of Marlborough, Massachusetts, declared:

"Death is more eligible than slavery. A free-born people are not required by the religion of Jesus Christ to submit to tyranny, but may make use of such power as God has given them to recover and support their liberties... We implore the Ruler above the skies that He would bare His arm...and let Israel go."

The result of a mob of angry settlers confronting British soldiers on March 13, 1770, the Boston Massacre was a tragic if inevitable event that helped to accelerate the collision between colony and crown.

As a faithful and patriotic American I should appreciate its significance as a milestone towards my country's independence. I do, with qualifications.

In seventh grade, my American History class held a debate, presented to the class as if they were French dignitaries, over the justification of armed revolution. Two classmates, Brendan and Steve, argued for the United States. A third classmate named Niki and I represented the King of England.

Niki and I did well. It's not easy to assume a position that opposes both nation and conscience; not even revisionist historians can do much to weaken the rightfulness of human liberty or the legitimacy of its modern and definitive introduction by Americans. Oddly enough I remember little of the two-day debate beyond highlights (I invite uBlog readers who were present in that classroom, even those accused of "cutting" students seated behind them, to offer any anecdotes), but I can say with certainty that the British case was well-prepared and smoothly delivered. Our strategy would have been a defense of most of the King's punitive measures and a rationalization for the rest. On one hand we would press for calm conciliation with the colonists and on the other condemn them as unreasonable, ungrateful and unprepared for a war they had poorly considered. And we would tie them up in knots over their continued possession of black slaves. A classmate friend of mine, Dave, would use the second day's question-and-answer session from the floor to powerful effect, eliciting some angry mutters from our opponents.

For their part, I can also confidently say that the American argument was inconsistent when not off-the-cuff. Steve and Brendan were both very intelligent but Steve was a sour kid who seldom applied himself and Brendan, a born defense attorney, chose aggressive theatrics and rhetoric over reason. The result was Steve sitting silently for two class periods while Brendan stood on his chair and appealed for French support on the basis of American suffering, chiefly the five killed in the Boston Massacre. Almost exclusively, the five killed in the Boston Massacre. Paul Revere's engraving, shown here, receives from some foreign and leftist quarters a characterization as sensationalist libel that most of us would consider unfair. Brendan, however, armed with a photocopy of the famous print, dotted his presentation from start to finish waving it about, out of his chair, shouting, "Boston Massacre! Five killed! A dozen wounded! Cold blood!" Niki and I would make a point, Brendan would stare blankly for a second before jumping out of his chair to yell the litany again.

When the vote was cast, King George won, a poignant reminder that a matter can't be won on melodrama. Although Brendan's cheap stunts made the debate memorable — the next year I advocated and won Abraham Lincoln's case for the preservation of the Union but remember nothing else — they left a deep impression of New England's publicization of the Massacre as at best brazen and at worst, tawdry. Fortunately, revisiting history books over the last decade-and-a-half has nearly pulled out the wrinkle.

I hate to call this a first, but here it is: I dropped by the local Starbucks this morning to replenish the office's coffee supplies. It's been the Christmas season inside Starbucks' doors for the better part of a month, and with the season come the decorations, the special items, the tantalizing prices — and the music. I worked at the same Starbucks for three months of summer in 1999, then Christmas break, then for eight more months after my May 2000 graduation from college. Most of my coworkers made no secret of their contempt for one aspect of the commercial Christmas season: music that would chase them home and loop about in their heads, repetitive and incessant no matter how many compilation albums were alternating in the store's disc-changer. Me, I could care less; granted, I only endured one season from start to finish, but I've never succumbed to the cyncism of fatigue. Too much of anything will leave you numb.

That said, I do grow bored — maybe a little weary — with Christmas' traditional assortment of pop tunes. The most wonderful time of the year is not, for me, in the words of Bart Simpson, about "the birth of Santa Claus." Tunes about everything but the holiday's basis lack substance, and, as I see it, happen to also lack musical profundity and longevity. "Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree" is good for about five plays before I'll seek refuge through the tuning dial or any kind of distance put between offending speakers and myself. If you pitted "All I Want for Christmas is My Two Front Teeth" in an arm-wrestling match against "The Holly and the Ivy" it'd walk away with a sprained elbow. Starbucks' music complement was, for the Christmases of 1999 and 2000, heavily if not exclusively secular.

Today, I was surprised to hear a touching rendition of "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing" while waiting for my coffee beans to grind. It wasn't cloying, it wasn't obfuscatory: good gracious, there was a man who sounded distinctly like Nat King Cole, singing about "Jesus, our Emmanuel." If I were Christmas shopping it would have felt like shopping for — for Christmas. It was the very song that does not grow tired on the ears. I hope the entire compilation from which the song was playing was sacred music, top to bottom, and that it enjoys heavy rotation.

Only having flown in a commercial jetliner four times before last Wednesday, I have been in and around Cleveland-Hopkins International Airport as long as I can remember. From 1980 to 1995 my father's parents would fly in from New York City for Memorial Day, and for the few Mays they missed they'd make it up at another point during the year. I would almost always be with my family greeting Grandma and Grandpa at the gate, hugging and kissing and then walking as a group of six to baggage claim, and then retracing our steps — up escalators, down escalators, across squeaky moving sidewalks — to our parked car for a ten-minute drive home.

It's not every house that's built nearby a major airport. My father took advantage of it, bringing my sister and I planewatching a dozen or more times in the early 1980s. Before the Federal Aviation Administration got wind of it and shut it down, a bottle-strewn parking lot sat practically across the street from the airport — just a few hundred feet — from the 23-end of Hopkins' old Runway 5-23. Depending on the weather, jets often leapt from or landed on 5-23; or else they'd move perpendicular to us on the airport's east-west runway. It didn't take long for my father to point out every make and model of aircraft, every airline: the 727, 737, DC-10, and DC-9 were most common, with the occasional 757 and an assortment of turboprops and business jets; Northwest Orient, TWA, Republic, American, Eastern, United, and Delta were all represented. I learned them and committed them to memory, where they reside now. These were the days before quiet engines, and in that lot the sound from a jet passing directly overhead, not five hundred feet in the air, was deafening. It was wonderful. In the years after the parking lot, my father and I would sometimes go to the airport, pass through security and stand on an observation deck. It wasn't the same as those summer evenings under the roar of cigar-nacelled 737-200s, but we quickly learned that the howl of a taxiing or engaging jet from one hundred feet away is just as exciting to watch. Our last time on the deck, before the specter of September 11th closed it, was in 2000: unbeknownst to us, a massive thunderstorm crawled over the western horizon and swallowed the airport. It was a storm all the same, but pilots weren't deterred: as soon as the strongest cells had passed, a line of airplanes — including a freight DC-3 — flew straight into the rain and lightning.

Walking into Cleveland-Hopkins on Wednesday, the day before Thanksgiving 2004, was different than the few times I'd done it since 2001: once my parents and I passed security, we stepped into the airport I knew. The shops, the bars, the eateries, the restaurants; the stands and kiosques; the shoeshiners and the cart drivers; and of course the travelers. I could look in every direction and find a memory. Images, mostly; but each one very clear.

The lit poster advertisements on the wall brought back a flood of times passed. I thought of the ads themselves — if I couldn't name them off the top of my head, you might show them to me and I'd remember which was which. For so many years we'd pass them on our way from security to the gate to baggage claim to the exit. AT&T, IBM, the City of Cleveland; so many. Even old Ray Fogg, the builder, whose posters are still on Hopkins' walls.

Random memories persist. The book in the bookstore — the store still here, after all this time — I noticed over fifteen years ago that portrayed a tiger in a fighter cockpit, something I've since been told might have been a Wing Commander novel. Five years or so before that, I remember a host of waiting passengers settling where they could on a crowded day, some leaning or sitting against walls. A college-aged girl, overalls and backpack, hair pulled back, smoked a cigarette — back when you could, of course — not far from that bookstore. I remember passing her with my family once, then again; the second time, she'd finished smoking and had picked up a book. One of the last times my grandparents stepped out of the arrival gate, I distanced myself from the gaiety for a moment to watch us as a group; catching us third-person through a ceiling reflection, or turning to watch Grandpa talk to my father about the flight and Grandma catch up with my mother and sister. All that time, I made a point to remember it all, that one arrival. And I do.

On Wednesday, I alternated between my new issue of National Geographic and people-watching. A gateway to the world, it would seem, is the best place to see a face from every corner of the earth. Cleveland-Hopkins International isn't the busiest airport, so even on the eve of Thanksgiving people walked by not as a throng or a mass but in threes and twos; sometimes two groups beside one another. Sometimes singly; stewardesses or airport personnel.

At our gate was a cornucopia before the passenger compliment was twenty strong. We had a single man in his mid-thirties; two old women, one with an attendant and the other living young, talking on her cell phone and paging through the newspaper before strolling over to a side shop for a strawberry ice cream. There was a hispanic, a little younger than I, talking on a cell phone of his own — a thick accent — in a style of speech slightly too rough for public. But no one seemed to notice or mind. A blond, ruddy, block-skulled man with a buzz and his thin, willowy, olive-skinned wife sat with their two crew-cut boys. Three black children led by the oldest, a beautifully blossoming woman in her late teens with meticulous, shoulder-length cornrows who read a book while her sister and brother played a hand-held video game. "Hey, you're makin' me lose," giggled the younger girl. After twenty minutes, older sister took the three to grab something to eat. Two round-faced brunettes on one side of the gate seating were matched by two spindly, hatchet-faced blondes on the other. A fellow my age, stocky and tall with a shock of black curls, sat down as boarding time drew nearer. Then a portly blond woman. Three more single professionals. Two more families. Others. There we all were.

Work has put me into the sky on a single-engine airplane more often than I ever would have gone otherwise, but in my twenty or so aerial rides I've never lost the sense of the takeoff roll being such an act of brute defiance; that there is no grace in flight without sheer, ugly, forced admission. As soon as that 737-900 turned onto the runway the captain slammed the throttle, mixture rich, and the jet muscled its way down the wet runway; muscled into the air on two-wings' lift; muscled through the clouds, wind and rain. The cabin trembled a bit, jostling us in our seats as nature suggested we stay on the ground. The jet refused and the low ceiling enveloped us — and everything went white.

For all its poetry, the flight was a drag. Nature stopped making polite offers and went to flicking our ear. The seatbelt light stayed on, no refreshment cart rolled out into the aisle, and near ten thousand feet the captain announced that turbulence began at our position and ended at our destination of Baltimore International: we had simply chosen a crumby day to fly. We wouldn't even be cresting near thirty thousand feet — the wind was just too stiff. Indeed, the only horizon we got was a single gap between layers of floating grey slush. "It'll be bumpy all the way in," crackled the captain's PA. "We appreciate your patience." Things never got rough, but turbulence is turbulence. My father watched a graphic data readout on the cabin's overhead monitors; I read more of my National Geographic and my mother found ways to distract herself from nervousness. The stewardesses found a material show of gratitude, handing out cups of water and orange juice as the plane pulled itself out of the early winter rainstorm. Fifty-three minutes passed from our leap into the sky. Twenty seconds before touchdown, we saw ground again. As my father noted, the captain flared a bit too soon and the 737 dropped to the runway with a bump. We taxied. "And here we are," I said, grinning through my headache.

The ride home on Black Friday was majestic. Baltimore was clear and cool; we were expecting partly cloudy skies all the way into Cleveland. Up we went, a bit of turbulence as the 737-700 broke through one deck of altostratus and into another. Soon the first deck looked like the ground, a strange floor of day-old cotton candy. Tiny patches hovered over the rest of the tops; the sun shined everywhere else. For a few minutes, I could make out the contrails of a jet moving away from us to the southeast. It was soon gone. The seatbelt light ticked off, and after a light treat of the stewards' Sprite and pretzels, I unholstered my camera.

Upon descent, there was no partly cloudy sky waiting: as soon as we sunk into the layer that remained below for most of the journey, it was grey and more grey. But moments after the captain announced our position on final approach we dropped beneath the cloud ceiling, revealing white-encrusted suburbs a few thousand feet below and a distinctly grainy, grey haze between jet and ground — snow, the best of Cleveland weather from September to March. "I love this town," I laughed to my father as he craned his neck to see out the window. Final took a few more minutes, followed by a landing impact smoother than the majority of flight on Wednesday. We taxiied as light snow and sleet fell. "And here we are," I grinned, no headache this time.

Tonight was a long night — but a good one. My civil service commission oversaw a testing company deliver the city's entry-level police examination. We'd conducted an entry-level exam for the fire department in August ourselves, with good results. The firefighter's test involved ninety-odd participants in the city's community center; it was crowded. For the police examination, our chosen site was a nearby Catholic church's gymnasium, holding the nearly two hundred attendees comfortably.

When all participants were seated, before the testing company took over, I made a few announcements to the group without a microphone — it was the first time I'd talked in front of over one hundred fifty people in a while, and quite a wonderful thrill it was.

The fire fellows this summer were a talkative, goofy bunch, maybe a little ornery; out of season or simple temperament, our prospective police officers tonight were polite, attentive and quiet. I handed out packets describing a required agility test that participants take at a local community college to each fellow — or girl, there were about ten — as they walked out the door after completing the test. Down to the man, each thanked me and bid the few of us authorities standing by the door goodnight. A few addressed me as "sir," and at least one of those gentlemen was active duty military.

A fine group, a slice of my generation worth a little pride.

They say New Jersey has been put into play since the Republican National Convention. While I'm somewhat more inclined to agree with a New Republic writer's assessment that President Bush's foray in the Garden State — including today's speech — is a "head-fake" designed to draw Democratic resources from battleground states to safe states, these developments dovetail with my own best-case Election Day scenario. From a recent letter:

Bush wins with 53 percent of the vote after an eastern state upset tilts the whole picture. Mass hysteria on the left ensues. Geraldine Ferraro shaves her head in protest.

Maybe the Metroliner Effect, the profound shattering of Tri-State myths about Republicans, the right and President Bush, will prevail. Even if it does, the East Coast has its old school.

Celebrating my grandfather's birthday at his and my grandmother's house is my Great Aunt Toni: spry and sharp, a delightful Joan Rivers-soundalike who has lived in Flushing for nearly forty years, the City all her life. Speaking to my father over the phone last weekend, she asked about me and my sister getting along in life, so my father told Toni that I'm currently the president of my local Republican organization. Which led to the following exchange:

AUNT TONI: (beat) Michael's a Republican?DAD: Well, sure, Aunt Toni; so am I.

AUNT TONI: (beat) You're a Republican?

DAD: Yes, Aunt Toni.

AUNT TONI: Oh, that's all right. I don't vote anyway.

We love you, Aunt Toni.

This is a continuation of my mention of Goethe yesterday.

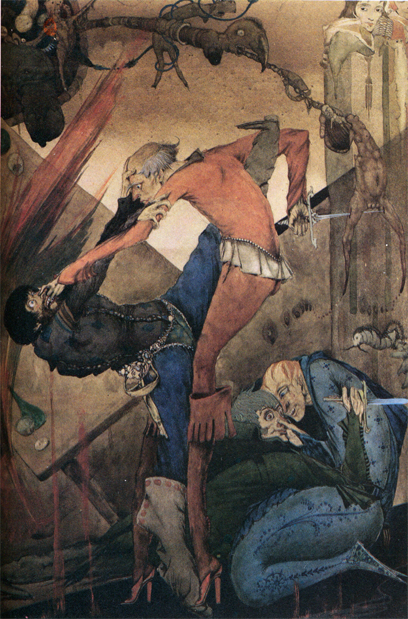

In 1984 or 1985 my aunt was dating illustrator John Jude Palencar (now my uncle). She had purchased (or he had given her) several books to which he had contributed, and every time my family visited her apartment I'd run straight to the books, curl up in a corner and feast my eyes on the surreal, macabre and fiendishly enjoyable work of Uncle John and his colleagues. One collaboration was for a Time-Life Books series celebrating folk tales, mythology and fantasy, called the Enchanted World Series. In the first book, Wizards and Witches, Uncle John offered rich, finely brushed and deep-shadowed acrylic paintings of Manannan Mac Lir and "the Black School" which were, naturally, favorites. But I was always more greatly drawn to the pages retelling of the Damnation of Faust. Loosely based on the Goethe play, the book set its story to four watercolor paintings by Irish stained glass artist and illustrator Harry Clarke from a 1925 edition of Goethe's Faust — a copy of which sits in the Cleveland Public Library's special archives, one that I've held in my hands. Clarke is not well known at all in the art world, but those who are familiar with him will immediately recognize his stylized, elfin human forms and penchant for visceral, almost biomechanical ornament that predated H.R. Giger by four decades. He was sought out to illustrate stories calling for elegant, unnerving images and succeeded wholly with his paintings and ink drawings in Faust.

One of the four watercolors is of "Auerbach's Cellar in Leipzig," where Mephistopheles tricks four drunkards into beating one another senseless. Clarke was able to capture the bewildering violence as Goethe intended it, I think: grim and gory but lurid, almost salacious in its devilish manipulation. "The demon smiled" with Faust in a safe corner, goes the book, while "young men fought like beasts." Watching flesh controlled by evil is not a pretty sight, and I see no distinction between the hysteria of this tragic scene and the short, savage, meaningless lives of the terrorists and thugs fighting our men now.

Faust. I do not imagine I know aught that's right; I do not imagine I could teach what might Convert and improve humanity. Nor have I gold or things of worth, Or honours, splendours of the earth. No dog could live thus any more!

ON CLARKE: Keep in mind that I was six and seven when first exposed to this stuff. The macabre made quite an impression on me — a good one, I think, as I took to a sort of figurative abstraction in my own art and in some understandings of the world as early as junior high. Funnily enough, I brought the book Wizards and Witches into a portrait class in college. Our professor, Jerome Witkin, asked us to describe a stirring portrait and explain its significance. "Auerbach's Cellar" isn't exactly a portrait but it was a powerful study of the heart, and had kept me stirred for fifteen years — so its selection was a natural one. Said Witkin, whose work is equally otherworldly (link not entirely work-safe), "uh-huh. This explains a lot."

My maternal grandparents came in from Michigan today for dinner at my parents' house. The last time I saw them was for my sister's wedding two years ago; it's been a long time since we just visited, and the conversation was accordingly rich. They didn't know I had taken twenty-one credits of music during undergraduate; I didn't know that during a trip to Florence, my grandfather found evidence suggesting his family did not originate in Agrigento, Sicily but Rome. Like any good Americanized Italians, we ate pasta in meat sauce followed by apple pie and strong coffee. And we talked and talked and talked.

The picture was taken as the three men goofily discovered just how tall each of us was; I was in mid-sentence, explaining to my mother how to handle the Olympus camera when it went off. Fair enough.

I'm proud to bear my mother's maiden name as my middle name.

Digging through my archives for source graphics, I came across posters for my old band, the Concord (whose fully recorded album will, one day, be available for aural consumption). Click for a larger image.

Granted, Instapundit was making a point about Walter Cronkite's blinkered, elitist hypocrisy: but along the way Glenn referenced a two-part interview with the creator of roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons, Gary Gygax (Part I and Part II). D&D is a game people who spent their single-digit years in the 1980s heard about more than actually played, Saturday-morning cartoon show notwithstanding.

My introduction to the game, over the initially strong objections of my mother (who, before Snopes.com, had no way of dispelling the urban legend of D&D's fatal consequences), was sophomore year of high school. It was a standard, four-to-five player campaign with classmates in one fellow's basement bedroom. Good times were had, including a couple of all-nighters, simplistic as it was; our group played no more than five sessions over the course of an entire school year.

The next year I came into a group of friends — including my now-Albany-based buddy Ed — who enjoyed games. Our favorite pastimes were marching band and pep band events at school but after hours we'd enjoy frequent bouts with the card game Magic: The Gathering, and occasionally we'd try and start a roleplaying campaign. Everyone knew D&D. We were careful about how we played: the game had a certain reverance about it and we responded by almost always trying the latest epic fantasia somebody had dreamt up. Well-intentioned, those stories were never acted out in full, never to be returned to, our regular schedules quickly succumbing to the flurry of high school. So we tried one-off games in between the campaigns, rich with improvisation; games that, ironically, I can recall far better than our interpretations of Tolkien or Hickman. D&D could be bent to looser, make-it-up-as-you-go style. Some games, however, were better-suited for reckless abandon. Ed was well-versed in the now-defunct FASA Games' sci-fi/fantasy crossover game Shadowrun. Like ritual, our team of cynic cyberpunks would assemble and plunge into our favorite Northwest American dystopia, falling afoul of one zaibatsu-like corporation or another, ending the game in a ragged firefight.

I recall one quickly aborted attempt to start a D&D campaign with our circle of friends during the summer before I headed off to Syracuse University; planning took too much time and concentration too much energy. We wanted movies, local trips and easy games. Thus my high school experience ended leaving me more like the typical student than the twelve-sided-die-rolling dungeon freak. In what can be considered irony — or a testament to the game's relevance to young adulthood — I truly played Dungeons & Dragons in college.

That fall, a group of four played two sessions led by my roommate. Short but memorable: my friend Dan is both an unlucky dice-roller and a good sport; the six numbers determining his character's physical and mental worth were pretty low, but he bucked up and played the character as a hapless do-gooder. School kept us busy; we took a couple of ad-hoc journeys over the winter but little more. It wasn't until March of 1997 — spring break — that I finally won my money's-worth from the clutch of sourcebooks I'd purchased a few years earlier, and truly came to appreciate the game as a confluence of storytelling, teamwork and friendship.

At home visiting my closest friends — who were one year behind and still in high school — I was invited to lead a game with their roleplaying group of seven or so. That evening after supper I brainstormed and scribbled notes for about an hour, constructing a simple, open-ended courier's mission for an impromptu adventurer's party. I look back at the notes — literally, I still have everything — and marvel at the freeness with which I put together names, relationships and objectives. There's a sweet wistfulness in admiring a discrete idea before it became a colossal thing that carried great expectations; to admire its innocence.

I brought the notes to Ed's house. We played. My friends enjoyed the adventure so thoroughly that they invited me to continue it when school let out. That June, six of us began again and played through the summer; we played the summer after, and the summer after that. But that's another story.