I followed dinner with a viewing of Steven Spielberg's The Goonies. Having not seen the movie for a decade or so before tonight, I can now confirm that it originally succeeded on account of more than the repeat theater attendance of exuberant youngsters.

Spielberg matched the finest of one filmmaking craft with that of another. The screenplay transports an otherwise outlandish plot: pensive kids, propelled first by need and then danger, search for buried treasure. Eight young actors assembled for Goonies were together only once but their on-screen rapport surpassed the so-called Brat Pack, finishing at a distant second to the Little Rascals.

Any skilled director must have known what he got himself with the four leads — two rising stars, one sophomore from The Temple of Doom and one memorable no-name. They gave Richard Donner nuance in their delivery; looks and gestures of camaraderie beyond what was blocked out, and a minimum of treble squealing. Jeff Cohen, playing Lawrence Cohen, or "Chunk," had found at age — what, eleven or twelve? — a small mastery of one-man slapstick.

There was and is a musical quality to the movie's pacing and direction: gags repeated only for good effect, thrills multiplied en route to a respectably graceful climax. An unthinkable, wonderful reversal happens; a tear or two is plucked from you; and closing titles cross the screen. Goonies gets put away with the guarantee of being watched again.

Spielberg made a film that will age very slowly, verified by me, at least, in the meeting between the apostrophic dreamer and leader — little Mikey Walsh — and the crafty, centuries-dead pirate, when Mikey steps into the bejeweled captain's quarters, long since made a tomb. The boy speaks to a skeleton rogue with an eyepatch, and tonight it was grotesque and moving, which is how I remember it.

Last night was spent at the ancestral home. Drawing from memories of winters spent under my parents' roof, I piled on half a dozen blankets and fitted myself with a wool cap. There was only one interruption after lights out, that by the combined, stifling retention of heat from half a dozen blankets, one wool cap and a feline trio which made itself a living comforter at the foot of the bed.

Wide awake but fervid, and so perhaps of somewhat impetuous judgment, I stumbled down the hall and broke the sleep of the occupants of the bedroom at the end of hall — leaving only when the question of my having tightly closed the door to the church after Christmas Eve service, something I couldn't, for the life of me, place in any certain memory at four-thirty in the morning, was answered in the affirmative. To bed I returned, minus cap, pajama shirt, worries, and one of three cats.

This morning, the gift exchange around the tree began the latest it ever has, about nine-thirty. Coffee, juice, chocolate, light breakfast on holiday plates; all intercalated among the unwrapping, thank-yous, laughs. I got books, books and more books. And one copy of A Charlie Brown Christmas, which is said to be as vital to the season as that from which it is in spirit derived, the Bible.

No lunch — chips and York Peppermint Patties took care of any lingering hunger. We all got ready, retiring at three-thirty to my apartment for dinner and fellowship. My kitchen was finally cooked in, inspected and cleaned by my mother, which is a little like having royalty christen with a bottle across a hull. I taught my father the card game Magic. The game is intuitive but complicated, and he started out from a position of disinterest. When the old man grew eagerly impatient with my tutorial I should have realized that he was two steps from catching on — three out of four rounds went to him.

The evening ended sweetly at half-past eight. I write this now, then I will nurse coffee with cream, and then Christmas, God bless it, has passed for one more year.

Reader A.B. asks about my family's Thanksgiving traditions.

Here in North Olmsted traditions are both simple and longstanding. As extended family lives hundreds of miles away in at least two directions, the dinner at home, like other holidays, has rarely been more than my immediate family of four and a guest or two. With some exceptions, like 1993, when Comedy Central broadcast the third of five Mystery Science Theater 3,000 marathons, someone will turn on the Macy's parade so it can play in the background while food is cooked. Invariably the parade will become so insipid that someone will mute it, but by then thoughts have turned to nonce appetizers — dried beef wrapped around the ends of scallions, sour cream as an adhesive. When I lived at home I would hide away for the rest of the morning, maybe play a computer game; in fact, one Thanksgiving morning I memorably beat a favorite, Nova 9. Come noon or one, the hen is ready, and my father's carving work sits girdled by mashed potatoes, stuffing, sweet potatoes, greens, biscuits and cranberry something-or-other. Dinner is followed by coffee, and then conversation.

Did you happen to know that a replica — a fully functional one, apparently — of Edinburgh museum's Pembridge Great Helm can be purchased from one of several retailers? I didn't, until recently. Fantasy swords I was familiar with, as I have held a few belonging to a friend, but mock armor made with regard to historical accuracy never occurred to me as a commodity; though perhaps it should have.

Weapons and armor of infantry and cavalry up to the martial domination of firearms have always been a fascination of mine; a pursuit more enthusiastic than scholarly, certainly, but long-standing. As much as I have done to learn and memorize the protective wear of a soldier, particularly the European knight and the evolution of his complement, I have drawn from the most persuasive accounts those many errors accumulated between the incorporation of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy and present day, the course of over a millenium. Particularly grating for historians is the impression that a knight was clad in plate armor from the start (he wasn't, not until about the 15th Century) and that a full suit was so cumbrous that, as depicted in Laurence Olivier's Henry V, he mounted a horse only with help from a crane — a fabrication dispelled as easily as donning a suit and moving with no more restrictions imposed than if in fireman's gear.

Best understood, of course, when the armor has been pounded into shape as closely to the original. Were it possible we might be spectators of the chain-sword-arrow-and-axe engagement documented in the Bayeux Tapestry — if not for the ablative carnage that was Hastings. So for a few hundred dollars the steel cap and nasal protecting a man's head and face from intentional harm can be yours, and Hastings comes to you. The cynic might just see metalworking curios. For others, between the dilettante, the smith and the scholar, history is not only tangibly preserved but a lost era revived.

After-dinner conversation, on an evening my parents spent as hosts for another couple, turned to children; my painting degree came up, and the visiting friends made known that they had never seen my collegiate work. Most of my paintings I left behind, so my mother had several from which to choose — this was one of them. I had nearly forgotten about it, painted between a pair of two- to three-hour sessions in 2000; a portrait of my mother.

I recently made the fruitful acquaintance of the member of Ubisoft Entertainment's video gaming team Frag Dolls whose sobriquet is Jinx. For about a year, ending in December, I was active on the forums constituting the Frag Dolls' online community. Three weeks ago, a fellow in that community was one of several recipients to whom I sent the latest mix of a song by my old band, the Concord. As was reported to me, he had the song both in possession and in mind when Jinx advertised her need for a musician. He told her about my hobby and work; she asked to hear evidence of it; he gave her the mix. Jinx thought enough of it to commission me, for a plenary submission of thanks and an undisclosed material reward that will arrive by post, to compose a short, thematic musical track and a few sound effects for the podcasting — or online broadcasting — that she has taken up as part of her work with Ubisoft.

The track I composed is here. When the request was first made, I thought of contacting Jonn and Gabe, two friends of mine, members of the Concord and writers of music both (Jonn nearing a master's in composition at the New England Conservatory). They compose more freely, extemporaneously, penning original tunes with ease. My labors in music are, like those in all other creative pursuits, amenable to purpose — profiting from inspiration but born of necessity. Musicmaking has always been intimate and especial to me; I am wary of the incidental melody striking another as frivolous. After regular work with a band ended in early 2003 I limited my efforts at new material to scribbling titles, concepts and descriptions of melodies and sounds on scraps of paper. And then, two weeks ago, a fine offer to compose. Well, OK — propensity won out. I did not wish to score The Frag Dolls Theme (Opening Titles). What I completed was received well, its method of construction worth explaining in this space.

Over ten years I have accumulated hundreds and hundreds of sound samples and effects that resulted from digital editing, the balance from five or more years ago in the salad days of recording — swept up by the exhilaration of actually recording on a higher order than a boombox. In the latter Nineties I eschewed, for a time, most proper musical instruments, instead swinging a homemade mallet at whatever object up to which I could sneak a microphone; separating and splicing, culling hiss or noise or the dullest sounds, then using digital effects to make whatever was left otherworldly. A few of them I inserted apropos for this song or that. Most of them I hoarded, waiting for precisely the correct application, as if a sound would be spent upon its placement in multitrack.

Listening to the two-minute piece, one can hear a single synthesizer progression that, as a motif, predominates. It topped a list I made of sounds that should have been titled "What Have I Got?" Nearly a dozen samples in all, they were selected from the list and assembled as a collage — the resulting style atypical for me. My accustomed writing is discursively chromatic and formally compact (such as this piece). The podcast track is succinct, even, but for the odd meter, simple.

The progression is called "Curesque," redolent of something Briton rocker Robert Smith's band might have played in the late 1980s, which Gabe created during a collaborative project he and I began in 1997. He played a simple melody on a keyboard with what might have been a harmonica module. Then, innocently enough, Gabe reversed the recording — instant ethereality. Then he left it alone, intriguing as it was, in favor of more productive material. Months later I adopted the sample with the rest of Gabe's library, and promptly lavished it with effect after effect. De-tuning chorus? Why not. Tremolo phasing? Can't go without. Reverb? Yes, two helpings, if you please. The summer afternoon "Curesque" assumed the form it would hold for six years I remember well, as my repeated playing back of the sample accompanied the approach and passage of a dark, brooding electrical storm. Infatuated with the transmogrification, I clasped the flush harmonies to the end of a song whose writing credit was Gabe's, where they really didn't belong. Now "Curesque" rests comfortably at the center of its very own opus; even in music production are there such things as reflection, contrition and reconciliation. That is, unless Gabe is outraged at the recasting, in which case I shall plead: Ha ha — too late!

The drum track's fundament is one measure from a session recorded five years ago. Eric, the musician behind the kit, was playing an early variation of a Concord song; an A-Major-in-five-four denunciation of the Irish Republican Army that came about when, two years before, I served coffee to a young man who identified himself as a stateside fundraiser for Sinn Fein. A virtuosic drummer, Eric expounded on the basic rhythm in several takes; one of which provided the key measure and another supplying the drum roll used at the ends of phrases. Cadences were played for subdivisions of five quarter notes; yet while the accents are strongest in that signature a given measure is suitable for, with respective elisions, four or three or two. Here I needed one drum loop, and in toto Eric's performance yielded an entire library.

Added to that loop were several close-miked drum samples. A kick, a snare; another kick and snare, suitably altered, for the piece's middle section; and a heavily distorted fill that is both phased and panned in stereo. A third snare drum strike came from a recording session in Athens, Ohio at the end of August, 2001. A dulcet colleague of a friend of mine attending Ohio University had thrown together a band and the band needed a sample disc for entrance to local venues. Intended for jazz, the kit on site sported a husky snare. I enjoyed the session — a generous offer given my inexperience — and that drummer could wield a stick.

The next sound is, if you can believe it, the classical group Anonymous 4. Rather, it was. Such alchemy would only occur to a recordist, as aforementioned, in this case that four women's voices performing sacred medieval polyphony are splendid when played forwards — so they must be sublime when reversed. Done. But, you see, I needed a rhythm complement to an old track of Gabe playing the electric guitar. Using a tool called an "envelope follower," which molds the dynamics of a signal around those of a second signal — my choice was the drum track — I broke the quartet into staccato sixteenths, then arranged it to play in syncopation.

Nomenclature fails the sound entering with the bass. Wary of mimetics, if I am to call it anything I call it the "Violator sound," an eponym drawn from British synth-pop band Depeche Mode's 1990 album — dotted, as you would expect, with a noise similar to this one. When a sine wave makes a glissando from a frequency near the highest reaches of human hearing (20 kilohertz) to one approaching the lowest (20 hertz) in less than 200 milliseconds, it creates a sound appropriate for electronic music when played singly; ineffably conducive to the appeal of same when played in multiples, like two succeeding 32nd notes.

There was an opportunity for humor in an inhale-exhale sequence of anacrusis and downbeat, and I took it. A college friend, one Sergeant Daniel Kissane of the United States Army as last I heard, volunteered his services when I began to toy around with electronic music in the fall of 1998. Those who know Danny will find the "exhale" downbeat sound's original recording characteristic.

I would say, in the words of a bawdily enterprising proprietor, I do not play but rather operate a guitar. Chords, melodies, and singing while strumming and plucking are techniques of which I am capable — you want finesse? May I please introduce you to someone who is not me. With my acoustic guitar in an open D-tuning, the B-string tuned downward to an A, leaving only tonic and dominant, I added to the music two pairs of phosphor bronze accoutrements: jangly rhythm parts, a capo set at the sixth fret and eleventh fret; and a couple scrapes with a brass slide, one musical and the other, well, expressive.

The terms of contract for this undertaking were loose; it is implicit that the original work is mine but that it may be used indefinitely to introduce Jinx's podcasts. What more to indite between yourself and one whom you esteem in person and profession? Were I to be chided over the impracticality of working for nothing I would refer to what I told Jinx: In the spirit of generosity (pro bono work is edifying) and self-interest (I now have for myself an infectious tune made of odds and ends that once lay useless) I composed the music and sounds happily expecting appreciation in return. That and satisfaction, each of which I now have in munificence.

ON APPRECIATING APPRECIATION: Thank you, Jinx.

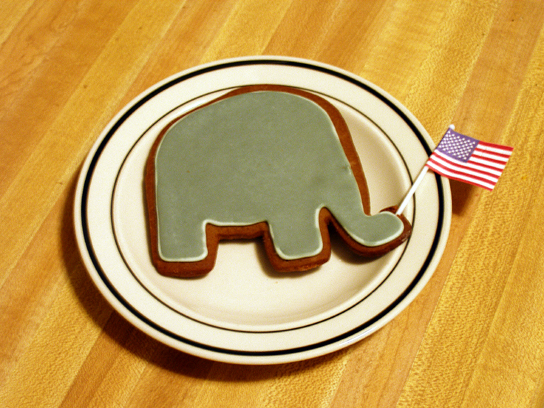

I went to the Republican Christmas party under the vague and sanguine assumption that no greeting was expected of me. Fifteen minutes before the last guest of forty arrived, a member of the board for which I serve as president informed me that, in fact, my check for dinner was not enough, and that I would need to sing for my supper. I sat down on a couch off to the side of the chattering room, memorized the list of city officials that had been handed to me, sipped from a glass of lemon-lime, collected my thoughts and placed them in order. After a delightfully garrulous opener by the gentleman who will keep the club's books in balance, I delivered a brief address. Following is a faithful recollection of those remarks:

There are those who would tell me that I have no reason to introduce myself, but those who know me know that I am one who stands on ceremony. My name is Michael Ubaldi, President of the North Olmsted Republican Organization, and I am happy to welcome you to our gathering tonight. We are here to celebrate a year that was at times trying, at times rewarding; one which sometimes ran a little long and sometimes moved too quickly for proper planning. But here we are. Now, before we all sat down I saw all of you talking and laughing, meeting old friends, new friends, and others. We are graced with the presence of public servants, who I will introduce now. [I introduced them in turn by name and office.]Now, among those names are a few people who belong to a group to which some of us would refer, euphemistically, as The Other Party. But tonight we forget that. We are all citizens of North Olmsted and, dare I engage in effrontery, we are all Christians; and these days usher in the Yuletide. It is with these twin sentiments, these two inextricable sentiments, fellowship and the anticipation of the coming of our Savior, that I leave you, so that we may enjoy the good times before us.

Of course, there was an exception: the fellow who notified me of my elocutionary duty is Jewish. I offered him a light apology later in the evening, as he sat across from me at the corner table, nursing a bottle of Chardonnay to my cup of coffee with cream. He has jokes about his laxity, so I offered my own about People of the Book, the one about the rabbi and the priest.

FIRST WARD FOUR ELECTION WORKER: Can I help you?

UBALDI: Ah, yes. First name "Michael." Last name "Ubaldi." That's you-bee-ay-el-dee-eye.

FIRST WARD FOUR ELECTION WORKER: (smiling) You're president of the Republican club.

UBALDI: I am.

SECOND WARD FOUR ELECTION WORKER: (growling, three-quarters facetious and one-quarter grave) Young people shouldn't be Republicans.

UBALDI: Of course they should. Many young people should — preferably all of them. (exit, right)

"I will never volunteer again," he lied.