If imitation is a gesture of admiration, synthesis is a fecund marriage of emulation and interpretation. The Japanese celebrate Christmas with every ounce of supply-side jolity as the broader American observance — while adding to the holiday a few of their own distinguishing characteristics. When Yuletide arrives, Santa scubas.

Cue Entrance of the Gladiators. The 39th Tokyo Motor Show, a fortnight-long world revelation of all things that roll on motor-driven variations of the wheel and axle, is now underway. Japanese designers often proceed uninterrupted from laboratory logic to the convention dais, form following uninhibited intent so closely that the showpiece is what many other designers would be content to leave as a curious maquette, a paperweight, on the edge of their desks or drawing boards, safe inside the office — too embarrassed to present straight out of the sketchbook. For Japan's automobile industry, then, there is éclat in a thoroughly ludicrous concept car.

Placing a bag of flour on top of a cutting board and two rolling pins normally results in Mother's praise and polite request for the missing items' eventual return. Nissan tried it and got "Pivo." An electric-powered people-mover, Pivo's distinction is its bulbous, revolving cabin which shall, the car company promises, bring an end to terms such as "hood" and "trunk" — and the need to back out of a driveway. When scuttling about town, families of three will be pleasantly acquainted with doubly large windows and the element of yaw. On which side does one fasten bumper stickers? Both; you may now choose twice as many. What happens when the cockpit swivels perpendicular or opposite to Pivo's forward bearing while on the interstate? Ensuing high-velocity hilarity. The car's wheels do not allow for horizontal motion, so parallel parking will remain an automotive tradition.

Placing a bag of flour on top of a cutting board and two rolling pins normally results in Mother's praise and polite request for the missing items' eventual return. Nissan tried it and got "Pivo." An electric-powered people-mover, Pivo's distinction is its bulbous, revolving cabin which shall, the car company promises, bring an end to terms such as "hood" and "trunk" — and the need to back out of a driveway. When scuttling about town, families of three will be pleasantly acquainted with doubly large windows and the element of yaw. On which side does one fasten bumper stickers? Both; you may now choose twice as many. What happens when the cockpit swivels perpendicular or opposite to Pivo's forward bearing while on the interstate? Ensuing high-velocity hilarity. The car's wheels do not allow for horizontal motion, so parallel parking will remain an automotive tradition.

Toyota describes "I-Swing," its roundabout answer to the Segway, as "emotional." The wheeled hair dryer chair is built to reflect its single operator's mood or clothing — feeling fire-engine paisley today? I-Swing can oblige. Intended for pedestrian use the vehicle can simultaneously reach faster speeds and channel Artoo-Deetoo by extending a third, front wheel. The Japanese mentality for robotics is very much at work here: It is reported that Toyota wishes to use "artificial intelligence" for I-Swing's adaptability; and a spokesman referred to the scooter's development as a process of "evolving," rather than "refining." We know that Toyota is excited about I-Swing's transformation of the daily commute. Judging by its prevailing color, is I-Swing?

Toyota describes "I-Swing," its roundabout answer to the Segway, as "emotional." The wheeled hair dryer chair is built to reflect its single operator's mood or clothing — feeling fire-engine paisley today? I-Swing can oblige. Intended for pedestrian use the vehicle can simultaneously reach faster speeds and channel Artoo-Deetoo by extending a third, front wheel. The Japanese mentality for robotics is very much at work here: It is reported that Toyota wishes to use "artificial intelligence" for I-Swing's adaptability; and a spokesman referred to the scooter's development as a process of "evolving," rather than "refining." We know that Toyota is excited about I-Swing's transformation of the daily commute. Judging by its prevailing color, is I-Swing?

Diphthongs bring a nice cachet to dignified roadsters (ask Rolls Royce), so researchers at Keio University in Tokyo named their creation — the fastest electric car on Earth — "Eliica." Clocking nearly one-third the speed of sound, the eight-wheeler confronts the stigma of battery-powered cars as slow, unmaneuverable and unattractive; while embodying the characteristics of inconvenient refueling and exorbitance. Lead designer Hiroshi Shimizu, seeking commercial and political support, is yet confident that those who want their very own bullet train will have it.

Diphthongs bring a nice cachet to dignified roadsters (ask Rolls Royce), so researchers at Keio University in Tokyo named their creation — the fastest electric car on Earth — "Eliica." Clocking nearly one-third the speed of sound, the eight-wheeler confronts the stigma of battery-powered cars as slow, unmaneuverable and unattractive; while embodying the characteristics of inconvenient refueling and exorbitance. Lead designer Hiroshi Shimizu, seeking commercial and political support, is yet confident that those who want their very own bullet train will have it.

For all of tomorrow seen today at the Motor Show, presenters remained human. This could mean that the bond between car and driver is inseparable — or else there is simply fine-tuning to do before the inevitable. Do androids dream of electric streetrods?

Just days after Junya Watanabe's jagged, lithe Sid Voguish and contemporary aesthetics are again piqued by the Tokyo-Paris axis. German composer Richard Wagner is considered by many — including a friend of mine — to be the pearl come from 19th Century Romantic nacre. How else to immortalize the narrative genius of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen than with world-class voices and unforgettably weird costumes?

The cautious eye finds the opera's principals Mihoko Fujimura (Japan, Fricka) and Jukka Rasilaine (Finland, Wotan) monochromatic, indigo, wearing shower curtains as dickies and atlas-shelf bookends for hats. That silky voice in the backroom atelier of our minds interjects and corrects: No, such muted abstraction is a great tribute, perfect in its contrast (visual minimalism against sonic floridity) and, like all things Apollonian, conceived for timelessness.

CLARIFIATION, JUST BARELY JAPANESE: Fujimura and Rasilaine were rehearsing for a production at Paris' Chatelet Theater.

A taste for the abstruse and, by extension, clothes no one will wear outside of a chic fashion show is the vice shared by all liberal democracies, so the growing reputation of Japanese designer and student of the postwar apparel school Junya Watanabe for widening the rift between art and life can at least be appreciated in terms of solidarity. Or is that commiseration? Watanabe chose this week's Paris festival of pomp to unveil his latest creation that would, said observers, "bring back punk."

Punk would protest at being doubly misunderstood. Once is preferred, as any upstanding anarchist prides himself on bewildering the establishment with his rebellion; twice is intolerable, for it means the establishment has gotten on fine without him, warmed to the litany of empty calls for revolution and has decided to integrate him in spite of it all. The malcontent is no longer condemned: he is an amusing caricature, perfect for exclusive markets. Anything he yells now only adds to expectation, the quaint little vandal.

Punk would protest at being doubly misunderstood. Once is preferred, as any upstanding anarchist prides himself on bewildering the establishment with his rebellion; twice is intolerable, for it means the establishment has gotten on fine without him, warmed to the litany of empty calls for revolution and has decided to integrate him in spite of it all. The malcontent is no longer condemned: he is an amusing caricature, perfect for exclusive markets. Anything he yells now only adds to expectation, the quaint little vandal.

So Watanabe tailored a set of outfits, taking postmodern loutishness from memory. Feet? Heavy and ponderous black boots. Bottom? Something torn, something black, something white, something red; most of it appropriated. Top? See "bottom." Head? Spiked half-helmets; plastic wrap over the face. The wrap? — oh, that would be Watanabe's own jab at common sense, his nod to the convention of defiance. The eccentric headgear, the overgrown scalp locks, are what seem to have brought the most eyebrows into puzzled misalignment. And? Perhaps they dramatize the first glorious microseconds that follow drilling a hole in the head of the Grecian Discus Thrower, inserting a stick of dynamite, lighting the fuse and stepping back to arm the high-speed camera. Or they could be a 21st-Century answer to the Statue of Liberty — a crown of spires without the Harbor girl's fuddy-duddy uniplanarity. One critic imputed Watanabe's "deconstruction" to politics, though irony would be the better choice, street urchin incorrigibility now swishing up and down a catwalk at a private Paris party.

There was the rare and rewarding sighting of an elusive Architeuthis by the Tokyo scientific community's subaquatic paparazzi, a contrived encounter that cost the subject giant squid and gained researchers, journalists and exotic seafood restauranteurs exactly one tentacle — but a collection of Japanese headlines and press pool photographs without robots is like a literary commodities market with no one shouting the price of Holsteins from across the floor.

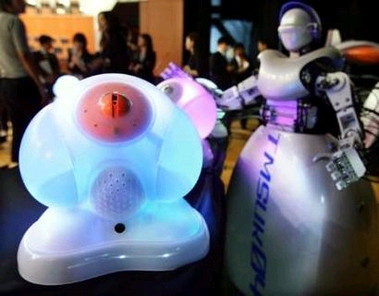

So we will regard the recent Tokyo presentation by Tmsuk Co., Ltd., former subsidiary of food processing manufacturer Thames Corporation and a youthfully independent Japanese robotics company, whose contributions to man's 21st-Century Pygmalion labor redress Tmsuk's offenses to Western pronunciation. Tim-sook? Ta-missuk? Tmsuk doesn't say, possibly because addressing the company itself becomes less important as one inspects its thirteen-year legacy in — all together, now — working "to create a safe and comfortable society in which people and robots can coexist." In 1993, Tmsuk posted TMSUK-1 at the Thames headquarters front desk as a mobile greeter; TMSUK-2 served tea, chatted about the weather and notified staff when it was due for a recharge, all in a charming dialect. By the end of the decade, Tmsuk produced the bell-skirted TMSUK-4, capable of varying degrees of directed and autonomous movement and activity.

It was TMSUK-4 that introduced Roborior, the company's commercial overture to cutting-edge Japanese households. Christened from a compound of "robot" and "interior," the squat, white, globular machine — oddly cherubic, if with a fleeting resemblance to the lethal excursion pods from 2001: A Space Odyssey — is a likely competitor of Mitsubishi Heavy's Wakamaru. Entryways, valuables and pets are all under the aegis of Roborior, which sends a live video transmission to its masters by cell phone. The unit is said to emit a soft glow, drawing those nearby into "a relaxing mood." Judging from a corresponding pool photograph that phrase may be a euphemism for "trancelike docility." All the better: for over ten thousand dollars more, Wakamaru is programmed to stand guard. If an LED anodyne can prevent the unfortunate burgling of an heirloom, home theater components or even little Gongoro, well then, let intruders see neon pink, blue and purple haze.

Introduced to Japan in February 2002, Microsoft's Xbox gaming console met and conquered the island nation's video entertainment market with all the grandeur and sempiternal glory of Kublai Khan, circa 1274. The Japanese, it turns out, do not care for corporate interlopers and care even less for corporate interlopers with consoles whose game libraries appeal far more to the rather matter-of-fact tastes of Americans. All the zany titles on Nintendo, Sega or Sony arcade systems to which Westerners have pointed and laughed over the years, upon discovery through word of mouth or serendipity, are a very telling exponent of Japanese gaming culture — and the most likely destinations of spending money from Japanese wallets.

The second-generation Xbox 360, scheduled for a rematch with Japanese consumers on December 10th of this year, benefits from four years' insight and a collection of financially didactic bruises. Microsoft is publicly confident, announcing the Xbox 360's victory three months before launch. The Japanese are reportedly still skeptical, four of five turning up their noses in a recent poll held by Famitsu magazine.

So? The men and women working under Bill Gates have always been good at keeping mum, so the software imperium's grand strategy may not be apparent until the Xbox 360 tries to embrace the island with a faceted, aluminium-polymer-silicon grip. But considering the good electoral fortune of Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi — whose intrepid campaign to privatize the country's postage-and-savings conglomerate included a head-turning commercial endorsement some ways back — and the above photograph from the Tokyo Game Show 2005, Microsoft is not about to dash a master plan with a breach of foreign etiquette.

Glancing at the morning's site statistics, I noticed half a dozen referrals to the uBlog from a Google Images search for "Peko-Chan." Peko-Chan is the Fujiya Confectionery Company's trademark avatar, a statue of whom stands at the entrance of every Company retail store. When I documented the commercial character eighteen months ago I made a reference, in the press photo caption, to the obvious risks of leaving a jumbo-sized cartoon figurine accessible to the hands of the disreputable, the obsessive or the practically joking.

One look at Google News explained the spate of Peko-Chan entries:

A 39-year-old man was sentenced Wednesday to seven years in prison for stealing Peko-chan dolls, the trademark character for major confectioner Fujiya Co., that are traded at high prices among collectors. Peko-chan, the trademark of confectioner Fujiya Co., welcomes customers at a shop in central Tokyo in this photo taken in April 2004. The company says some 30 of the dolls have been stolen nationwide since January.The Yamagata District Court ruled that Hiroyuki Cho ordered a collaborator to steal 15 life-size dolls, worth about 1.1 million yen in total, from restaurants and shops in Gunma, Saitama and Yamagata prefectures from May to July last year. Cho, unemployed, lives in Takasaki, Gunma Prefecture.

Prosecutors had demanded 11 years in prison as violence was used in some of the attempts to steal the dolls. ...Although Peko-chan dolls are not for sale, they are traded among avid fans, and life-size ones can reportedly fetch more than 100,000 yen.

Two American equivalents are immediately apparent: the stone goose, which resides, in varying seasonal and holiday attire, on the front porch of every craftswoman homemaker; and Bob's Big Boy, which adorns, double-decker burger with everything on it in hand, the front walk of the eponymous restaurant chain; both of which regularly fall prey to pranksters. But neither of those sell for nine hundred dollars on anyone's black market — and no one in the United States will face eleven years behind bars for swiping one (or a dozen). You know the refrain.

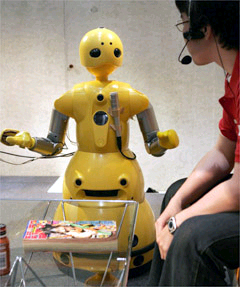

In the tradition of automative humanitarians, Mitsubishi-Heavy Industries Ltd. robot Wakamaru — like a caution-yellow, beveled Two-OneBee — was, as it were, designed and manufactured to serve. Wakamaru is a homebody, capable of visually recognizing those with whom it amicably chats through a lexicon worth ten thousand words, and programmed to assume domestic roles that range from valet to nanny to sentry. Having promoted itself at public events such as the Expo 2005 this past June, the droid is part advocate, too. In the compact and adorable Wakamaru the industry has a propitious example of, as late British humorist Douglas Adams put it, "your plastic pal who's fun to be with." Another distinctive and functional Japanese robot, another cadenza in the vaulting rhetoric of anthropomorphization:

Mitsubishi-Heavy said it would be the first time a robot with communication ability for home use has been sold."This is the opening of an era in which human beings and robots can coexist," it said.

Wakamaru will retail for fifteen grand, so reconciling Household Budget versus Machine may be the first order of business.

HAVE YOUR ROBOT PICKED OUT?: A sci-fi future, according to Extremetech, is a bit closer than previously imagined.

Arrival, Hong Kong; Departure, Japan. Hello Kitty brought a record-breaking crowd, estimated at over one thousand Chinese fans, thundering in to see her "Hide and Seek" exhibition on opening day. What was inside? Hello Kitty — as art, as phenom, as merchandise and merchandise and more merchandise. Pictured above, lead Sanrio designer Yuko Yamaguchi stood by her creation "Fairy Hello Kitty," the latest in redefining a product by catalog number and limited-edition volume. Hello Kitty as mercurial sprite is as good as any illustration for the appeal of a demure cartoon cat heretofore inscrutable: Sanrio leaves a single, subtle variation on an old theme under its pillow for which this pop culture pixie will exchange, overnight, goodness knows how, several million dollars in profit.