Skip past the prelude for the Ballad of Samuel Alito that dragged on for two months, through the first largo phrases bowed by the United States Senate Violin Section (all of them concertmaster) and go straight to the sforzando leitmotif of the Democratic Party — that inalienable right to legalized abortion.

Charles Schumer, the baritone from New York, performed a duet in the Judiciary Committee hearing late Tuesday afternoon. Gesturing, he delivered a response to every one of Judge Alito's cautious explanations of whether the Supreme Court nominee still believed that, according to a letter written to Edwin Meese in 1985, "the Constitution does not protect the right to an abortion." Do you stand by that statement? intoned the senator. In as many words, Alito said that as a judge, he would consider the facts before him. Five times. Six times, Schumer leaned forward, hands out, and sang in triplet anaphora: I'm not asking you about stare decisis, I'm not asking you about cases! Response from Alito, and again: I'm not asking about case law, I'm not asking about stare decisis! Back and forth it went. I'm not asking you this, I'm not asking you that; Your opinion on Roe, please, in five seconds flat!

Samuel Alito did remind the chamber audience that no part of the Constitution, not one of its twenty-six amendments, has a word on abortion. But if only he had looked down, grinned, rapped his knuckles on the table and admitted Yes, Senator Schumer, and I will instruct the tailor to embroider that very phrase inside my robe. Maybe the judge truly is circumspect twenty years after the heady Reagan days; or just practical. That he refused to answer directly could not be deception, so difficult is it to convict a man of gainsaying when he is caught in a farce. Three acts through, the question of abortion was raised in each, when Samuel Alito's Democratic antagonists could hear the decorated judge's opinions per appointment if they simply saw to his confirmation — Antonin Scalia offers his opinion all the time.

Though the associate justice is recognized for his strict jurisprudence and lacerative wit, it should be the pellucid genius of Antonin Scalia that rests in legal annals. Scalia's intricate reasoning is set in plain words, in humor and slang often delivered in speeches, which those of us belletristic find comforting inasmuch as someone equally devoted to clarifying truths will practice articulatory distillation to our conjury. And what must chagrin people who think Scalia should not say much of anything in any manner is that he sounds so damnably reasonable.

What keeps morality? Not law, we learn from Scalia. That imperative lies with legislators and citizens — those who pass a statute and who must abide by it. If a court extracts rules from figurations — emanations, penumbras — the obligation to beneficence and deliberation on the part of the electorate is waived. "The Bill of Rights," the associate justice addressed to the Manhattan Institute eight years ago, "was a small exception to the innovation of 1789, which was democratic self government; that an intelligent society should debate these issues, even these important issues; persuade one another and govern themselves. That was what 1789 was about." Mustn't a democratic state perforce be run by a moral society? Yes. How is that best preserved? Settling cardinal disputes by majority vote. So reasonable.

When one places abortion under scrutiny the two positions are not "choice" and "life" but Roe and not-Roe. After that, precedent strengthens an argument but hardly makes it convincing. Scalia, again, calls Roe's bluff. Constitutional right to abortion? No. To life for that inside the womb? No. "Reading it as a lawyer I think the Constitution says nothing either way on it." And, consequently, neither should the Supreme Court. What about in a state legislature? A ballot box? Pass a law for or against, Scalia tells us. See? Reasonable. Fear of Roe overturned can only be fed by a mistrust of one's fellow citizen and one's representatives, as if a judicial retraction would propel every last state to a ban on the medical termination of a pregnancy.

Polls show that most Americans are comfortable with abortion existing in one or more forms. But there are considerations finer than the Supreme Court's stare decisis. When the lady tells the gentleman that there will soon be a baby in the house, from Donna Reed and James Stewart onward, nobody has turned to the other wondering who she's talking about.

Post-Roe, states would go their respective ways. I believe the use of abortion as a contraceptive to be executed only in cold-blooded conceit. But I find just as repugnant pressing a woman to carry a violative germ to its efflorescence, superintendent to lasting — indeed, living — injury. Nor would I abandon the progenitor. Were a law or a constitutional amendment for Ohio to proscribe only that first practice, and allowed a doctor to kill a fetus in the name of the exigent triumvirate — rape, incest, birthmother near death — I would not challenge its passage. And I would likely see greater concurrence where I live than San Francisco or Tulsa — where Californians and Oklahomans would codify their own judgments. Well, when Senator Schumer put on his little sing-song yesterday, did he consider that mediative power of federalism?

Arriving from afar, a foreign observer might conclude that the Supreme Court is a social arbiter, parties competing to compose the bench so that it carried out their policies. Stand back, goes that notion, and hear what the court has decided. Following Scalia's lessons, the wisdom of that court becomes as definite as an originalist's Constitution: What is unenumerated, judge for yourselves, and don't listen to us. Certainly not what Schumer wanted to hear, and a pity Samuel Alito would have been tossed out right there for saying it.

Rod Dreher, editorialist for the Dallas Morning News, has written in the London Times' Sunday edition about "crunchy conservatism." A book of Dreher's on the subject will be published in February, the author's Times article to herald the release. Crunchy con? Dreher and his wife's epiphany came with the realization that "[S]ome of the things we uncritically admired as conservatives, or at least accepted without protest, served to undermine the family and the institutions that we would need to raise good children." Where to? Out-of-the-way stores, institutions and associations. Why would anyone take flight? "Humankind will always seek after the good, the true and the beautiful." What stands in the way? Drudgery and material riches, the "huckster society," argues Dreher.

One sees a characteristic smudge to his delineations. Gaudy mercantilism, the grotesque that Dreher makes out of rightism and American tradition, has been the property of the left for decades. Popular culture, contrary to Dreher's claim, preaches cynicism and socialism — anyone under 40 years old should know from personal experience. By way of Wal-Mart and asphalt, Dreher accuses capitalism of spoiling the land. Really? Why is a less productive China disproportionately more effluvial than the United States — because industry alone consumes, whereas private interest, market incentive and the common good temper industry for husbandry. One may as well blame the invention of electricity for house fires.

Dreher writes that conservatives are suspicious of big business. No, historically the right distrusts unions and populists that succor incompetent and insolvent establishments. A rightist is a "strident libertarian"? — hang on, wasn't the Republican Party being led astray in Washington by tax-and-spend bureaucrats? Or something? I occasionally buy organic lemons and green onions from the grocer but if iconoclasm is lagniappe I have yet to bring that home, too.

It is as though Dreher observes the right secondhand, so there is disjuncture in Dreher's asking the right to contrive "economic and social policies that would make it easier for traditional families...to form and stay together." What more can a legislature do than to mitigate tax burdens, resist the alloying of marriage and prevent entitlement programs from discouraging commitment in the home and neighborhood? How is the complication of law for one purpose any different from that for another? How to extricate via intrusion? Dreher doesn't elaborate, so we must guess. Compulsory weddings? Enforce a fifteen-mile radius beyond which neither spouse may be employed? Relegate annulment and divorce as felonies with a mandatory sentence of house arrest and a marriage retreat?

As inchoate as Dreher's proposal is its intended delivery. Anybody who talks of "anti-political politics," jettisoning laws of contradiction, misinterpreting the reluctant compromises that are made between political and ideological opponents, all to organize some kind of transoceanic powwow, is peddling autocracy or sophism. It is sophism for Dreher, who must be waiting for the new order to try out anti-political politics. He is the one, recall, who compared President Bush's Supreme Court nominee Harriet Miers to Caligula's horse.

Concluding, Dreher reaches for the absolute, quoting Peter Kreeft: "Beneath the current political left-right alignments there are fault lines embedded in the crust of" — of what, the American way? No, beneath "human nature," that "will inevitably open up some day and produce earthquakes that will change the current map of the political landscape." One does not invoke mankind without implication, and Dreher's aphorism makes the "crunchy conservative" overture an affront. "The ideals we stand for," Dreher writes, "are the most real things there are." Much more real to him than forbearance, diligence and consistency.

Last August, Rod Dreher's ululations in the days after Hurricane Katrina's landfall — drawn from spurious media reports — reflected a man unacquainted with the injury and tragedy that attend mortal life. There is ideal, then there is practice. American rightists have been leading, in Iraq and Afghanistan, something quite like Dreher's pursuit of "idealism" and "common purpose," insofar as every honest man on every continent will live and work in peace if his government allows. After three years in Iraq, the universality of peaceful and democratic self-determination looks promising but the experiment has been laborious and, at least for contemporary hearts, costly. Those for whom "the good, the true and the beautiful" among "humankind" in the Near East was a velleity have disavowed the enterprise. Who is one of them, who has called Iraqi renaissance a "debacle," a "rolling disaster," all part of President Bush's "frog-march[ing] liberal democracy around the globe"? Rod Dreher.

Rod Dreher can derogate free markets, proprietors and customers. He can have his farms and hamlets. Impelling revolution he will find difficult. With whom, to what end and by exactly which means? Have we got to wait for the book? And Dreher had better tighten up his perorations so no one confuses the ideals therein with the passions of certain men and women who, though they agitate for betterment not so far removed from Dreher's, are supernumeraries in his most glorious, impossible dream.

It was suggested to me by a friend that the uBlog series "Four on the First," a monthly presentation of four albums I own or might have recently enjoyed, now having run two years, might be made richer with brief reviews done retroactively. In fact, I had been weighing the idea myself and, upon the request from a trusted member of my little audience, prepared to begin at the start of 2006. Around the first of every month, now, each album of Volumes I and II will be addressed in turn. I won't be publishing any new sets; there is no need. Volumes III and IV will return us to a library of eight dozen musical works — and give me time to discover some new pop music, since I had nearly run out.

Drawn from Life, Brian Eno (2001) — Inimitable and indefatigable, Brian Peter George St. Jean le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (known more economically as Brian Eno) collaborated with Peter Schwalm on this addition to his two-decade ambient and electronic oeuvre. The album is predominantly minor-key and while not quite dark, Eno and Schwalm's arrangements and production are melancholy. Legato synthesizer leads settle into downtempo drum loops that, with a nod to trip-hop, match subsonic pulses with doctored snares and glossy rhythm sequences.

Drawn from Life, Brian Eno (2001) — Inimitable and indefatigable, Brian Peter George St. Jean le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (known more economically as Brian Eno) collaborated with Peter Schwalm on this addition to his two-decade ambient and electronic oeuvre. The album is predominantly minor-key and while not quite dark, Eno and Schwalm's arrangements and production are melancholy. Legato synthesizer leads settle into downtempo drum loops that, with a nod to trip-hop, match subsonic pulses with doctored snares and glossy rhythm sequences.

Track four, "Like Pictures Part #2," is the album's catchy standout; over a trudging, exotic beat with off-time handclaps can be heard digitally stretched vocals of 1980s multimedia postmodern pop doyenne Laurie Andersen. Andersen's lyrics are as laconic as they are whimsical, the stage artist once again having fun at ontology's expense. Like her or not, Andersen is singularly intelligible; contra pitch-bent gibberish on sixth track "Rising Dust," toddler babble on ninth track "Bloom" and vocoded chorus on tenth track "Two Voices." For its part, "Bloom" is the most immediately faithful to Eno's thesis, a calm exchange between man and child recorded in a kitchen or family room to the effusive serenade of a string ensemble, the seven-minute piece kept in time by a cardiac thump and its reverse set end-to-end.

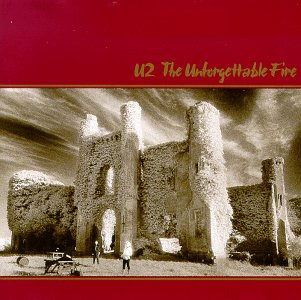

The Unforgettable Fire, U2 (1984) — What happens when Brian Eno is obligated by contract to direct the creation of an album by a rock band approaching mega-stardom? Said band is never the same again. After three records by producer Steve Lillywhite in as many years, U2 had moved from precocious garage rock to devotional garage rock to political garage rock; with Daniel Lanois, Eno set up with the Irish quartet in Ireland's Slane Castle and rolled tape, cultivating the rapport and compositional inspiration responsible for the 1987 éclat The Joshua Tree and what casual fans would thereafter insist as prerequisite for a "U2 song."

The Unforgettable Fire, U2 (1984) — What happens when Brian Eno is obligated by contract to direct the creation of an album by a rock band approaching mega-stardom? Said band is never the same again. After three records by producer Steve Lillywhite in as many years, U2 had moved from precocious garage rock to devotional garage rock to political garage rock; with Daniel Lanois, Eno set up with the Irish quartet in Ireland's Slane Castle and rolled tape, cultivating the rapport and compositional inspiration responsible for the 1987 éclat The Joshua Tree and what casual fans would thereafter insist as prerequisite for a "U2 song."

It was in Slane that Dave "Edge" Evans transmuted the sound of two electric guitar strings fingered at perfect fourths and fifths with syncopated delay into a categorical style; that Larry Mullen, Jr. used rack toms as high-hats; that Adam Clayton began to sublimate his bass performances into loyal, deep-toned chord roots and passing tones; and that Paul "Bono" Hewson found another half-octave to his vocal range. But for singles "Pride" and "Bad," the album is a lesson in the limits of experimentation according to schedule and budget; it is rough and uneven. Still, it is an achievement and a favorite.

Phases of the Moon, CBS Records/The China Record Company (1981) — As a remedy for those of us who once believed Chinese folk music consisted of clumsy twangs set at parallel fifths, CBS Records' Earl Price assembled recordings of music performed by Communist China’s Central Broadcasting Traditional Instruments Orchestra and published the collection under the title Phases of the Moon. A compendium of traditional music, Phases traverses the country and its history, setting 20th Century compositions alongside melodies from Xinjiang and Yunnan provinces; presenting a motif from the Peking Opera, borrowing from the Uygurs and Mongols. The compact disc's booklet includes a narrative by Price, a poem by Bo Juyi, documentation for each song from the China Record Company and ink drawings of native instruments.

Phases of the Moon, CBS Records/The China Record Company (1981) — As a remedy for those of us who once believed Chinese folk music consisted of clumsy twangs set at parallel fifths, CBS Records' Earl Price assembled recordings of music performed by Communist China’s Central Broadcasting Traditional Instruments Orchestra and published the collection under the title Phases of the Moon. A compendium of traditional music, Phases traverses the country and its history, setting 20th Century compositions alongside melodies from Xinjiang and Yunnan provinces; presenting a motif from the Peking Opera, borrowing from the Uygurs and Mongols. The compact disc's booklet includes a narrative by Price, a poem by Bo Juyi, documentation for each song from the China Record Company and ink drawings of native instruments.

Pulled open between nation and culture, however, was the interstice through which Price allowed politics to enter. Days of Emancipation, a rapturous anthem led by a virtuoso, double-reeded suona, is so rousing that listeners will need to remind themselves that it is no less insidious than "Deutschland uber Alles." Days is introduced in the notes as composer Zhu Jianer's 1950 melodic transcription of the "joy and excitement" Chinese farmers were said to have expressed at communization that would leave 30 million dead. One can't help but imagine, set to this music, a film of serial stills that follow the peripatetic evangelism of the Red Guards to come sixteen years later, leaving for history such wonderful vignettes as a man having the hair shorn from his scalp for the inexpiable offense of styling his coiffure after Chairman Mao's.

Yet because Days of Emancipation enchants as gracefully as a tune from any other century, it should be preserved for a nation truly emancipated, removed from its original purpose, words perhaps added — reclamation by recondition, as Martin Luther did when he seized libationary volkslieder for the church hymnal. Then Chinese music would be not for militarists or communists or another autocratic dynasty, but for the Chinese people themselves.

So, Peter Gabriel (1986) — If you say "Peter Gabriel," most Americans who grew up in the Eighties will respond "Sledgehammer" or "In Your Eyes." These two songs' escalade of singles charts brought commercial permanence to Gabriel who, if not as assiduous as Brian Eno, rivals his fellow Englishman's proclivity for the exotic and eccentric. An audition of So when familiar only with its two vanguard singles — or even the third, "Big Time" — and expecting a horn section or African percussion on every track, may end in surprise. The album is delicate, sparse, bright and synthesized; some might say antiseptic. It invited the talents of a dozen of the day's best recording musicians but employed them fastidiously: Police drummer Steward Copeland is credited with playing high-hat for the opening track "Red Rain." If making an eclecticist radio-ready was the objective, of course, we can say two decades on that So was a surpassing triumph. That Daniel Lanois co-produced the album not two years after an earthy and rugged The Unforgettable Fire attests both his manifold director's temperament and Peter Gabriel's artistic prerogative.

So, Peter Gabriel (1986) — If you say "Peter Gabriel," most Americans who grew up in the Eighties will respond "Sledgehammer" or "In Your Eyes." These two songs' escalade of singles charts brought commercial permanence to Gabriel who, if not as assiduous as Brian Eno, rivals his fellow Englishman's proclivity for the exotic and eccentric. An audition of So when familiar only with its two vanguard singles — or even the third, "Big Time" — and expecting a horn section or African percussion on every track, may end in surprise. The album is delicate, sparse, bright and synthesized; some might say antiseptic. It invited the talents of a dozen of the day's best recording musicians but employed them fastidiously: Police drummer Steward Copeland is credited with playing high-hat for the opening track "Red Rain." If making an eclecticist radio-ready was the objective, of course, we can say two decades on that So was a surpassing triumph. That Daniel Lanois co-produced the album not two years after an earthy and rugged The Unforgettable Fire attests both his manifold director's temperament and Peter Gabriel's artistic prerogative.

Not a week after Iraq's parliamentary elections it has been determined that life in the country will not go forth happily ever after. The Independent Electoral Commission of Iraq announced early returns bespeaking a landslide victory in Iraq's central province for the United Iraqi Alliance coalition. Obloquy from rival parties followed, some of it as bad as what comes from the Democratic National Committee, including a claim from former Prime Minister Iyad Allawi that somebody in the IECI had divulged information ten days early. Disenfranchisement? Fraud? Riots in the streets? Not quite. Though Iraqi citizens are reportedly only a bit less perplexed than the IECI, tallying plods forward.

The West is, reliably, on the verge of making too much of this. Opponents of Iraqi liberalization took the news smugly. Patrick Cockburn has celebrated Iraq's parliamentary elections by twice declaiming the country in a state of disintegration. Cockburn is a killjoy epigone of Robert Fisk's, who while dismissing political triumphs in Iraq as "spurious turning points" has been pertinaciously writing in leftist publications about Iraq tumbling into bedlam since at least March of 2003, apparently on the outside chance that he will wake up one morning and not be wrong. His prognostication may be suspect.

There are sensible uncertainties. Last week William F. Buckley, Jr. cautioned against precipitate jubilation, as "To Iraqis the very idea of an election was novel." Perhaps in January, to elect a National Assembly differing greatly from the governments previously assembled; and again in October to ratify the constituent body's production. Novel for the third time, after a year of the Iraqi press complaining of Baghdad's incompetence and venality? Overlooked is the courage required of a voter over there to simply walk to his precinct — surely this is not ephemeral. Detractors and skeptics of the new Iraq and its Western benefactors impute tyranny and strife to collective efforts of an entire populace, that when problems arise "Iraqis" are to blame. If that charge were condign, balloting in Fallujah, Ramadi and other places along the Western Euphrates would not have taken place. Liberty's foe has always been a tiny minority reveling in duplicity, intimidation and violence. Even the probably terrorist-linked political groups in the December 15th election, abhorrent to Iraqi Sunnis like the liberal brothers Omar, Mohammed and Ali Fadhil, represent the interests of few.

And if armed supporters of one party draw beads on supporters of another? Then Iraq would have some street fights between partisans, and combatants would be rounded up by federal authorities to public applause. Contrary to the perception delivered by leftist media, bloodletting is not a national pastime. God forbid, would we see another Abdul Karim Qassem, a coup? No, for three reasons. First, whereas the British in 1921 took a hindquarter from the Ottoman Empire and sat down a king, Americans established a native representative government. Corollary to that, there is in Iraq an egalitarian volunteer army and transcendent patriotism where once there was not. Third, notwithstanding those strengths, the American military is still in town.

Iyad Allawi's statement offers some explanation for the odd counts. Voting preference isn't geographically proportional. Count Chicago last, and Illinois will look as if its twenty-one electors will be Republican. Numbers have changed, most of them in favor of the United Iraqi Alliance's opponents. Some Iraqis won't be happy with the elected parliament, but losers never are; that is the price paid to play a fair game. Besides which, minority coalitions will have four years to bargain, wheedle and campaign. They can follow the example set in the oldest democracy in the world, where the opposition party now regularly consoles itself over losses with yarns of conspiracy and treachery, and has managed a fair job harassing the president and his party's congressional majorities.

Good can come of this. Who is a statesman, who a demagogue? One legitimate concern is over the sincerity of a few parties; Baghdad may respond to an exigency by finally disarming a few political militias. Iraqis will sort it out. They have endured terrorist gangsterism, contumely from leaders of some of the nations they wish to join and the doubt concomitant to reconstruction. The country they have helped build is hardly endangered by a kerfuffle.

The Democratic Party's choice of timing to demand a retreat from Iraq was poor, the third and final ballot to inaugurate an Iraqi constitutional democracy having now been met with supporters' optimism and skeptics' grudging acknowledgment. This was the second breach of Washington etiquette for modern warfare, the first committed in late 2003 when Democrats extended the reach of hard politics from the edge of American coasts to that of propriety. Three weeks ago a Democratic representative from Pennsylvania, identified by the press as a "hawk," gave up the ghost on the floor of the House of Representatives. Democrats hesitated, then moved to support the congressman and harness what seemed like public momentum to flatten President Bush and his party. They were instead thrown into a bizarre position, akimbo and untenable.

The congressman from Pennsylvania, a turbid old warrior, has trouble deciding whether he thinks Iraqis either are or are not in a civil war (they are not, he has said both) or whether Iraqis by and large either tolerate or detest the American presence (they tolerate it, he has suggested both). The man has also shown why veteran status does not necessarily confer strategic acumen, as he proposed our troops defeat the enemy by leaving the chosen battlefield and settling five thousand miles away. The day after his speech, House Republicans turned around and put to vote a non-binding resolution on immediate withdrawal that was defeated, 403-3.

Democrats protested, their bluff called. They could well have been shrewd at that point, arguing that an emerging picture of success justified progressive American departure — appearing loyal and practical while getting their way. But then they would a) accredit Bush, which b) runs counter to every utterance from every prominent Democrat for months, save c) Senator Joe Lieberman, who d) does not answer to, and is contemned by, the left proper, which e) appears ready to be remembered as having stood in the way of freedom abroad.

So, since Thanksgiving, leading Democrats have declared Iraq a failure and say they want out now — but not quite out, or now. Howard Dean, Doctor of Parisology, was last heard trying to explain why he didn't believe Iraq was unwinnable when he said on a radio broadcast that the idea of winning was "Plain wrong." House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi embraced retreat a fortnight after repudiating it, and following her announcement that the balance of her caucus supported retreat she would not call the question because "A vote on the war is an individual vote." Senator John Kerry, accused of circulating apocrypha on national television, had his office release a statement that, more or less, impugned anyone with the temerity to question the authority of a serviceman (and former Senator Bob Dole, of the 10th Mountain Division, turned in his political grave).

What cause have backbenchers to pull troops from the front? There is room to complain, if you want — but to surrender Iraq? Hardly any. Casualties are low for the million soldiers rotated in and out of theater over three years, and if repeated polls recording strong morale were insufficient, high reenlistment and recruitment rates show confidence among those who have and who will serve.

The Iraqis fight our common enemy, defending a way of life with which they have just been acquainted. But opposition Democrats generally refer to Iraqis in a third person reserved for inanimate objects. And for the disavowal of Operation Iraqi Freedom to be politically successful — I will be charitable here, Democrats may not have guessed this — no Iraqi must live to tell the tale. If that is Democratic Party policy, it is something of an indifference to liberty itself. Were they to regain federal power, what would Democrats do about Syria and Iran; or democratic progress in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan and elsewhere? What happens five years from now, when Iraqi democracy and civility has been asseverated?

Casting off a certain people as savages is all well and good until you actually run into one of them. How might members of a Democratic administration or congressional delegation greet elected representatives of Iraq, whose country, their party argued, should have been left in the hands of Saddam Hussein — or campaigned to abandon to the enemy, which converged, lymphocytic, on a foreign body politic? What does a Democratic envoy say to someone whose liberation and societal revolution culminated a military campaign he publicly consigned to dysphemisms? Oh, hello! I really didn't expect to see the likes of you outside of a documentary, as part of some crazy escape like we saw attempted by the Boat People — in your case, I guess, Camel People. Well, no need to think about such things. When I talked about a "mistake" I didn't mean you, but, you know, the circumstances. Things turned out, though I'd have done them differently. So there we are! Does one say something like that, or does one simply say nothing at all and, when pressed, forswear any impertinent statement?

And to whom will that appeal stateside? There is the adage that what makes Americans magnanimous also imbues ambivalence, so that every two or four years the electorate will concern itself with trifles and vote, with respect to party, towards equilibrium. History shows otherwise, particularly from this country's last great moral disambiguation, that of which men had certains rights inviolable: The crumbling of the Whigs, the inception of the Republicans, the split of the Democrats; Republican victories in nine of eleven presidential contests and Republican Houses won in 14 of 23 midterms, from Confederate surrender until the party's 1912 Conservative-Progressive split.

Today comes moral clarity again. Iraq's parliamentary elections will be held tomorrow, but diasporic voting in fifteen countries has gone on all week. Security is tight at polling locations yet lines are long because Iraqis will finally popularly rule their country — they have been seen smiling, laughing, cheering, crying, right index fingers colored purple. Yesterday a television news crew from — surprise — Fox News filed a report on Iraqi exiles in Michigan. Towards the end of the brief an old expatriate, curly grey hair and thick glasses, holding her inkstained finger aloft to huzzahs from onlookers, cried "For Iraq!" Facing a news camera, the woman continued in an accent embossed with trills.

"Without America, we couldn't accomplish this, we couldn't come to this. Anybody who does not appreciate what America has done," she said, eyes wide, stepping back and raising her voice, "and President Bush..." She looked down. "Let them go to hell." The Democratic Party is halfway there.

A travesty cannot be made something genuine, even by popularity, but then in the United Nations truth comes second to fiction. Two years after meeting in Tunisia to build a consensus on how best to enact a UN mandate over the internet, the World Summit on the Information Society reconvened last month in the same north African police state, led by United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, for another go. If it was assumed that the transnational bureaucracy would be chastened after indictments for corruption leading to the sustentation of Saddam Hussein, methodical abuse in protectorates, neo-Nazi merchandise commemorating Gaza's Arab settlement — well, what is thought sordid and disqualifying elsewhere is just another rowdy olio in the year-round production at Turtle Bay.

American journalist Claudia Rosett, who might be Holmes if the UN Secretariat had nearly the competence of Moriarty, reported on the summit in Tunis. One hundred seventy-five countries were represented; in three days 40 statements were delivered and documented. The event's collective declaration is sinuous but transparent: American control of the internet's structure and delegation presents an obstacle to "poverty eradication strategies" and "digital solidarity" among "developing nations" and "development partners." What does the WSIS want? Divestiture.

The internet is, like most of modernity, deceptively simple. Two years ago I had the opportunity to choose another company from whom the domain name "figureconcord.com" would be leased — at the same time I switched this website's hosting company. I thought I would manually effect the change myself. I had a hell of a time doing it, confronted by a substructure far more involuted than a casual operator's experience, which is like opening a shutter and gazing through a window. Yes, what is all that, anyway?

As those of us with a working comprehension know, a computer whose content can be accessed remotely is identified by a unique, twelve-digit address. For ease of use, a given computer can be reached through an alphanumeric title. These titles are domains, which carry either "top-level" or "country-code" domains such as ".com" or ".us," respectively. These are leased to individuals by commercial and state entities that have been recognized by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority and IANA only, since a domain name ("figureconcord.com") is only useful if it points to one source of content (this website), just as you expect the phone to ring at a particular residence when you dial a number. IANA submits directories to ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers which, while no longer subjacent to the United States Department of Commerce, fulfills a sole-sourced contract. The internet's originator, therefore, is its arbiter.

"Many countries, privately, felt that the US was being generous in sharing the internet with the rest of the world," wrote Dr. Peng Hwa Ang, a professor from oligarchical Singapore, in a riposte to Rosett. But, Dr. Ang warned, countries supportive of the WSIS would tolerate the spirit of giving for only so long before they began a little "pushback." Why? Simple, reasoned Ang. "The US did not have to do an 'internet grab' because it already had the internet in its hands." Catch that? One who has must be receptive to those who do not and wish to take from him — even though he will never quite understand, since he can't exactly take from himself.

WSIS/UN usurpation is based on an allegation of worldwide ownership. The claim has an irredentist ring to it, which makes it all the more unctuous. The internet is almost entirely a product of the American demiurge, from defense network to web browser. What of foreign contributors? One may as well put forward that because of seminal contributions to aviation from Raymond Saulnier, Anthony Fokker, Hans von Ohain, Frank Whittle and Nikolai Zhukovsky, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey should cede LaGuardia Airport. The internet can be confused or misrepresented as a shared enterprise only because the medium transcends hitherto conceived modes of communication and production, and that the United States has invited the rest of the world to contribute and profit.

On that, it is not the fault of, say, the people living in dictatorships that full participation is impossible. Popular use of the internet is anathema to tyrants. Have you heard about the recently jailed Egyptian blogger? — for the first time in human history, a man could beam from Cairo to every last corner of the earth all things unseemly about his pharaoh (presently strongman Hosni Mubarak). Or have you heard about the thousands of Iranians skirting Tehran's repression, the most capable and articulate libertarian dissidents today? An unanticipated democratist windfall places the matter in terms of morality, liberty; national and collective security. In wartime, the internet is no different a proprietary technology than materiel, no less profound to human liberty than the Gutenberg Bible. The claim of any other party to assume control should only be worth the measure of capital it has expended under the foregoing terms.

How about these requirements for a country's sovereign control of domains: Receive from Freedom House or equivalent the highest possible grades for civil and political liberties for fifty consecutive years, then submit to the United States Department of the Treasury a $2 billion security deposit, then sign an affidavit pledging to encourage and preserve at minimum twelve thousand private websites which unequivocally maintain that the current head-of-state is a horse's ass.

Until that is worked out, the internet is a most valuable asset of the free world, a potent weapon against tyranny — and it must be left in American hands.

When I suggested in July that the Entertainment Software Ratings Board penalize developer Rockstar Games for violating the video game industry's sovereign rating system and subsequently inviting the vituperation of New York Senator Hillary Clinton, I appended the condition that a chastened Rockstar would yield the industry a more defensible position, and not a settlement.

What happened? A software company known well for its lurid products smuggled an X-rated, interactive sex scene into Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, a game owned by a number of teenagers who — according to the ESRB, which rated San Andreas "Mature" — should not have played it until their seventeenth birthday. The offending sequence, "Hot Coffee," embarrassed the ESRB and the Interactive Entertainment Merchants Association, which by near-universal retail representation pledges to enforce the ESRB ratings. It also attracted the attention of Hillary Clinton and Joseph Lieberman, who with a coterie of senators introduced the "Children and Media Research Advancement Act," or CAMRA, legislation devoting $90 million to the five-year vivisection of an entire industry.

The ESRB and the IEMA were obeisant, effectively driving the game from the market. But that didn't placate Clinton, and a 2005 study conducted by the National Institute on Media and Family — condemning the video game industry's cordon sanitaire as downright porous — was part of the senator's November 29th press release heralding a companion bill to CAMRA.

As announced by Clinton's office, the proposed legislation would not only anneal ESRB ratings with the force of law by banning sale of games rated "Mature" to minors but conduct audits to verify retail proprietors' compliance with ESRB ratings, and federally scrutinize the ratings themselves. The bill would empower a Federal Trade Commission investigation of the possibility that Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas was not an outlier but a bellwether, and Clinton's Sense of Congress would invest in the legislature authority to punish the development industry itself.

Video game companies are already wary of the collective notoriety brought by the meretricious capers of Rockstar Games. A system assigning legal consequences has been protested by the industry on grounds of its chilling effect, and — with film, literature and art industries operating virtually unrestricted — rightly so.

What stuff of American life is sequestered from youth? Juvenile consumption of liquor and tobacco can, of course, be prohibited by Congress through the interstate commerce clause in Article I of the Constitution. Video games, as goods intended for sale between states, would be subject to the clause but for their status as artistic expression, which affords them consideration and protection under the First Amendment. In several states a minor's purchase of or contingent exposure to obscene communicative items has been outlawed, at both municipal and capital levels, relevant statutes upheld by the United States Supreme Court — first in the 1968 case Ginsberg v. New York and seven years later in Erznoznik v. City of Jacksonville. Well, now Hillary and Joe would like to try from Washington.

There are two obstacles. First, the legal definition of obscenity has been for thirty-two years "Prurient, patently offensive depiction or description of sexual conduct" that is without "serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value." Prurience is central here, prurience an exclusive and sempiternal denotation of salacity. It just so happens that of the 957 games currently rated "Mature" by the ESRB, thereby judged unfit for sale in nine of ten retail stores to minors sixteen and under, only 39 ratings — 4 percent — were predicated on sexual content alone. Depictions of violence qualified the other 900-odd. Outside micrometric circumstances of fighting words and other incitement, lawmakers can neither silence nor restrict dramatized injury and death.

The Entertainment Software Association has reported that only 12 percent of all games sold in 2003 were rated "Mature" — increase that, for the sake of argument, to one-fifth, and the representation of potentially obscene games is still only tenths of a percentage. Prohibition for the one bawdy game per every gross? Out of the 1957 high court opinion deciding Butler v. Michigan in favor of a pulp peddler came a warning to legislatures that a sanction had better be proportional to the license it is designed to attenuate. Second, behind all this is the federal judiciary's insistence, shared from court to court, on "community standards" to determine what constitutes the prurient interest — which blocks federal override.

So? Clinton's twin bills are a hassle, not likely to be passed by Congress, signed by the president or accepted by the Supreme Court. Oh, but they are a hassle, and the industry ought to deprive Washington of an argument for expropriation in the public interest.

The advantage of choosing private supervisors over government regulators is that the freedoms of speech and press are expressly intended, and the free market best equipped, to provide a forum for the acceptance or rejection of expressions and productions. Video game makers and sellers can vindicate self-discipline. The Motion Picture Association of America's rating scheme, having endured for the balance of four decades, is an example of a reliable system when utilized by conscientious families, a standard to which the ESRB and the IEMA aspire — and can certainly reach.

What about non-governmental critics? The National Institute on Media and Family, entertainment industry gadfly, does not advocate censorship. Video gamers don't care for the Institute's statements about their pastime, and they resent the Institute's disapprobatory report being one of Senator Clinton's primary documents. Well, yes, it was rather convenient how one obliged the other, but popular antagonism is OK. If denigrating claims were by themselves cause for lawmaking Congress would long ago have interdicted every brand of paper towel that Rosie the Waitress proved wanting for capillary action.

This year's was a white Thanksgiving. Snow began falling on Wednesday just after noon, lightly, and with intermittent northerly gusts across Lake Erie white bands came nearly every hour or two, thickening when night had fallen. I swung by the local mall at eight o'clock that evening; upon making my purchase, I exited the building and ran into shifting walls of large, wet flakes. I wore no hat, and not twenty paces across the sprawling commercial parking lot one side of my face was draped with frozen slush, so I cocked my head to one side and navigated the way to the car — I always park in distant, open sectors of asphalt — by shutting my left eye and squinting through my right. A treble burst of wind punctuated the rustle of snow meeting earth as I walked forward. Cold but invigorated, from the heavens' descendant humor I took my own, laughing out loud at the peculiar sight for which I must have made.

In the fifteen minutes for my mall transaction a second, thin coat of snow settled on the car. Reaching for the scraper again, I turned the ignition, set window defrosters and switched on the radio. Cleveland's classical music station was broadcasting the recording of a solemn motet; gently repeated, a single phrase was sung through my brief labor, and the same when I finished, when I drove from the parking space and out of the lot, and when I shut the radio upon pulling up to my apartment. Thanksgiving Day saw an alabaster mix of fresh and wind-blown snow and ended still, with a nightfall temperature of sixteen degrees. Those were two special days, and yet the profundity of the experience was as much an accounting of the elements as its implication. Cleveland weather like this is exceptional for late November.

That is not to say northern Ohio is without its reputation. Striking up a conversation, seated next to me at the reception for my cousin's late September wedding in San Diego, the Fresno-born, erubescent wife of a cousin of the bride rejoined my answer to her first question — she had asked me where I lived — with the interjection "Br-r-r-r!" Yes, Greater Cleveland winters are cold and they are snowy but a city and its surroundings as an arctic retreat is a characterization better deserved by Augusta, or Syracuse or even St. Paul. Christmas has an odds-on chance of snow — Thanksgiving does not. In my twenty-six years' residence here, on only five of November's third Thursdays could one glance out the window and see white of appreciable depth. Therein, the foregoing implication. Five of twenty-six is twice the average established from records stretching back one hundred five years. The last thirty years provide for two-thirds of the region's measured Thanksgiving snowfall over the last century. That, and especially this lovely holiday week, is, against the orthodoxies of "global warming," weather that should not have occurred.

Dire portents become a tough sell when someone has got records in front, clear memories behind and the slightest faculty with statistical analysis. Weren't we tugging at the skirt of the Reaper twenty years ago? Well, when what could not be was in fact ten years later, the explanation was that it would soon cease to be, given a year or fifty. Two decades on, we hear logical contortions evocative of a double-somersault through five flaming hoops suspended eighty feet in the air while juggling knives: assurances that symptoms contravening expectations are in fact dispositive evidence of a purported cause. A few equanimous climate researchers, lost in a politicized field, have tried for years to inform the public that a) computer models can't predict anything decades in advance, and b) even if Earth is warming, it c) may, possibly, be traced not to industrial detritus but the spherical, thermonuclear engine 93 million miles from here, and, finally d) the Earth warmed and cooled many times before respective Henrys Bessemer and Ford, with far greater dynamics than is claimed contemporarily.

And there you have "global warming," styled as the desideratum of egalitarian science, in practice something like pruritus ani for the modern world. The best way to understand "global warming" is to become acquainted with "global cooling," the antithetical doomsday myth it succeeded. Swim with the current, they say. One constant straddles trends, that of traducing the industries of mankind — specifically petroleum and its use in the automobile. Internal combustion is to some the primary threat to life on our planet, and certain former Vice Presidents have joined in writing entire treatises set in this eschatological mode. Other texts, most of them history books, credit petroleum with the greatest revolutions in standards of living.

History is frequently off-limits to politics, so a sagacious company like British Petroleum decided to lose some headwind by euphemizing its name as "BP" and running commercials demonstrating the extent of an average citizen's memorization of "global warming" rote. The result is what you find asking passerby about Santa Claus: long on intellectual acknowledgment, short on logical proof by assertion. One almost suspects that BP executives are not at all converted, and grinning all the while, as the advertisements' interviewees are rather inarticulate about "global warming" and just what they propose be done about it. One woman, for example, guffaws that turning over her car would be "Like giving up chocolate." What?

British Petroleum is probably sincere about rendering its surname obsolete. Why shouldn't it be? Gas-electric cars boast a potential for 100 miles to the gallon. Markets, consumers and developers look forward to the transition from fossil fuels as one more step in technological progress, not Luddite or Marxist deliverance. The end of oil will be like any other upheaval in business or industry: Keep an eye to the future, a fresh resumé and, mutatis mutandis, your wages are still earned. None of this, of course, tempers the fury of those who despise the idea of livelihood determined by capital, risk, competition, failure, resort, reform or return; to say nothing of wild success.

Is the next revolution too long of a wait? There must be a way to console alarmists who jump at a temperature swing and see all storms as omens. After all, anomalous weather is a Midwestern hallmark — and an unexpectedly harsh winter, as this one may be, is something to be relished. No? Send them all off to Berkeley, then, where "global warming" consensus will be undisturbed, perhaps better contained, and where the weather is palliatively mild all the year round.

A doctor of mine has two miraculous dispositions, the first to briefly discuss politics with me during visits; and the second, as far as the war is concerned, to share my broad outlook. The appointment before last was just after President Bush's second inaugural address, and my doctor had been reading a book publicly attributed to Bush's inflorescent vision for universal liberty — The Case for Democracy by former Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky. Though he wasn't a partisan, my doctor said, he found the convictions of both author and president inspiring — their work's fruition appealing.

When my doctor walked into the examination room during my latest appointment this month, he began with "It's been a tough week, hasn't it?" Vice President Cheney's Chief of Staff, Lewis Libby, had been indicted that day by Special Counsel Patrick Fitzgerald for testimonial indiscretions. I answered that Yes, this isn't the best for the White House but the man is politically inert and the charges are unrelated to the alleged crime. My doctor pressed on as he sat down, warning me in advance that his confidence in assertive democratization went "up and down."

That day it was down. He wondered aloud if Iraq was better under a strongman after all since, as he saw it, the country's ethnic groups "hate each other." My doctor wished Iraqi liberals to succeed but judged the country "a mess," at a loss as to how well Sharansky's idealism actually worked in practice.

If someone is to dismiss Sharansky, it cannot be as a pampered notionist. Natan (né Anatole) Sharansky came to embrace and champion democratically afforded human dignity without once having experienced it himself, promoted his adopted cause with contumacy in a state where political deviance led to elimination or incarceration, chose the dark occasion of his years in the Gulag — particularly the many days of solitary confinement, an approximate perdition — to redouble his faith in something that for a lesser man could not possibly exist outside of the mind. Sharansky was freed from Soviet dominion in 1986, settled in Israel, and has since then braced and refined his argument for liberty. Only now is his native Ukraine emerging from a communist stupor, following most of the former USSR. Surely, after the man and his ideas endured such torture, wouldn't poor Natan have been the one to abjure? He never has, no matter how many readers of his books might.

Two exchanges struck me. On the indictment of Libby, I volunteered that Joseph Wilson — husband of inexplicably uncovered CIA agent Valerie Plame, reason for the Fitzgerald investigation — is a man apart in deception. My doctor seemed surprised that Wilson's public claims are lies start to finish: why Wilson went to Niger (God knows why), who sent him (his wife — not the vice president), what he learned (nothing extraordinary), who read his report (the CIA — not the vice president) and what it meant to the CIA's estimation (no change — Saddam wanted uranium). On Iraqi sectarianism, I offered Christopher Hitchens' recent confutation: neither Saddam's racialism nor terrorists' repeated attempts at inciting strife could alter or debase Iraq's astonishing consanguinity. Again, my doctor looked as if I were the first person from whom he had ever heard this.

My doctor is an intelligent and considerate man, however, and his last words on the subject — he wisely cut the talk short — were "We'll see." But something had gotten to him since we had last spoken, and more deeply than Sharansky. Judging by his factual paucity, it could only have been the left and the mainstream media. Look at polls, then look at congressmen chasing them: a false Iraq is now the country's prevailing definition.

Majority American sensibilities are then, for the moment, directly contrary to the high opinions of those in theater on our side, foreign or native. The son of my city's current safety director, an Army captain with Task Force Olympia in Mosul, came home safely. The father made the announcement at our local Republican party's November meeting. Morale is high, the son reported, and soldiers are undeterred but for "the press." Nearly everyone in the room understood: the aggregate of elite media, East and West, in oppugning the war, has resorted to broadcasting not events as they happen but a selective and specious narrative that ends in American defeat. I described the nature of this propagandizing — part anti-American, part illiberal and part pro-fascist — in "They Saw Potemkin."

Not a year ago I realized that information in press releases from Central Command were foundations for the more substantive (and less aggravating) reports from media agencies — the military would report for the reporters what happened, and reporters would ensconce those five sentences in eleven paragraphs of politically charged speculation. I began avoiding mainstream articles — the "independent media" — altogether. While I quickly noticed that political and military progress in Iraq continued even without a lugubrious running commentary, it should be somewhat alarming when one finds himself dependent on the government for information. But those lettered, syndicate journalists are no longer the only manifestation of a freedom of the press. What good is profession when you haven't done the work?

There are alternatives. Last week Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum stood with three men and one woman, amateur and freelance war correspondents, whose medium — blogging — was virtually unknown just four or five years ago. The lot of them was recognized by Santorum as having "communicate[d] the messages from our service men and women who are reporting very positive stories out of Iraq." Up until a decade ago these four might have been confined to the quaint station of the "Armchair General," Norman Rockwell's April 1944 cover art for the Saturday Evening Post. Yet they are not dabblers. Twice Santorum said that the four "communicate" news, as if the formal use of "report," fittingly enough, nowadays means "make up." Communicate, fine; they report as so the term was meant.

Michael Yon is a freelancer, embedded with Mosul-based Marines before the unit returned to the States. He is intent upon returning. He may be joined by Bill Roggio, a stateside observer who is gathering donations for his own embed tour and who, like Andi Carol and Steve Schippert, disputes the patrimony of gentry media by combing mainstream reports for useable information, comparing it with military reports and local observations and fitting it within the context of major maneuvers — and even the whole of the Iraqi campaign. That all of Santorum's guests of honor support the American military effort means their work is unflinching but morally sound and, too, accurate. They know the equivocation that bylined journalists call "neutrality" only addles.

Iraqis are themselves painfully aware of the obscurantism that would be their doom, and those with means have begun directly appealing to Americans. Take Kurdistan, in the northern reaches of Iraq that — having benefited from a decade safe from Saddamite influence, protected by Allied no-fly zones — is so peaceful, democratic, pro-American and rapidly modernizing that no mainstream journalist dares enter or report from it. Michael Yon did, and likened it to Italy. The other night a television commercial played during the evening news: on-screen, a procession of Iraqis thanking, through thick accents, Americans for their generosity and sacrifice. "Thank you for democracy," struggled one mustachioed, beaming man. If that weren't forward enough, the ad ended with the banner "Kurdistan: the Other Iraq," a website address in subtitles. The other Iraq — the one ignored by those who claim to bring you news.

A question asked with rising frequency, principally on the right, is whether Western journalism will survive the war. Already we can see that to watch and to tell is an act that anyone can do — that the conscientious can do best. Then one shall hope for the answer: No, not in its present form, and good riddance.

On the stark white cover of National Geographic's September issue is the African continent and above it, an enormous cover line reading "Africa — Whatever you thought, think again." The remonstration was surely meant to pique, but for a month and a half this subscriber left the magazine on his coffee table, untouched.

I have enjoyed National Geographic all my life, a subscription to it three years old this spring. I greatly prefer stories on the sciences, wildlife, archaeology and paleontology to the magazine's sociopolitical work; National Geographic's posture on the subject favors moral sterility over objectivity. This is especially apparent for stories about illiberal or despotic states, the magazine's analysis often very contorted.

If the Near East is the least free region in the world, the African continent comes in second. Bring a land rich in wonder, resources and human potential under alternating corruption and tyranny, and the burden of staggering modern atrocities, and once has a resounding tragedy.

National Geographic acknowledged the state of the African continent — its privations, but not so much the rather obvious root of its troubles. For the issue editor-in-Chief Chris Johns wrote of his hope that "Africa can be a model for the world in finding a balance between the needs of people and the needs of wild places." That is the position I suspected; why I left the issue on the coffee table. But the other day I moved the magazine and it opened to the "World by Numbers" section. For September was "My Seven," a short interview with 2004 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wangari Maathai of Kenya.

Wangari Maathai is a Western-educated biologist who is best known for her mass reforestation campaigns like the Green Belt Movement and acts of civil disobedience against Kenya's erstwhile authoritarian government. The occasion of the laureate's acceptance was marred by a public confrontation over her aspersive opinion on AIDS. Kenyans blamed their nationwide affliction on God, explained Maathai, and she felt obliged to enlighten them. What did she say? "In fact [the HIV virus] is created by a scientist for biological warfare...Why has there been so much secrecy about AIDS? When you ask where did the virus come from, it raises a lot of flags. That makes me suspicious." Oh, my.

Christians and Jews believe that the universe is a broken one, corrupted by treachery in the Garden, and that despite an abiding divine love men are subject to ravages of the earth. With the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth and the inheritance of the Gospels Christians believe that corporeal intervention is no longer necessary — no plagues, no burning bushes. Science cannot tell us exactly Why but it does tell us How, and at present science maintains that viruses are protein-encapsulated obligate intracellular parasites. For the faithful, that means poison fruit of salted land and not the work of Providence.

And not, for Heaven's sake, the product of a laboratory. Maathai did nothing but replace one superstition with another. Her mythology imputes the hand of men, which is a pretty serious accusation for — well, a scientist. It is one thing, in the hospital room, to reconcile an explicable malady as the way of the world and quite another to turn on the doctor since he did show up rather conveniently and is, after all, profiting from the circumstances.

What do we do about accomplished people, Nobel laureates, who have a calumnious side? South African humanist and leader Nelson Mandela, who won the prize in 1993, has of late lost his ability to distinguish between abominable dictators (Saddam Hussein) and democratic liberators (George W. Bush). Seventy-four years earlier you had President Woodrow Wilson, the democratist who was also a miasmic bigot. Can selflessness be blotted out by fatuity? Only if we are to expect immaculacy of the living. But it follows, then, that if we treat men as men we elevate to recognize — never to apotheosize. South Africans, plural, millions of them, toppled the National Party; Americans have as a nation stood up, fought and died for the freedom of strangers; and Wangari Maathai is, activism aside, but one who helped bring elected men to Nairobi, and what her tree-planting serves is agronomy.

But Maathai won last year's Peace Prize, and enquirers like National Geographic decided that a biologist must know statecraft, too, so among the September periodicals went a global promotion of the sophism that liberty can be had through the progress of things other than liberty. What other things? Two months ago Chris Johns spoke with Maathai in New York City. According to Ms. Maathai, there is a "critical link" between the environment and democracy. OK, there is, but in which direction does she think the equation goes? What begot what?

Turn to the magazine's one-page interview. Maathai was asked about the environment, empowerment, education, good government, sustainable development, employment and the future. Her answer to the first question (I will abridge each as fairly as possible) was sensible enough. Problems were "Actually symptoms of larger problems...Our country was so hungry for cash crops that...degradation of land was widespread." After winning independence from Great Britain in 1963, Kenyans endured forty years of a repressive, corrupt, negligent, one-party state before a democratic revolution in 2002. Freedom House, the most respected arbiter of polity, notes Kenya's "energetic and robust civil society," as well as its stalwart independent press — crediting the work of activists like Ms. Maathai, though it does not mention her by name.

It is in Maathai's second answer that we see how democracy and the environment figure. "[I] suggested we engage women in tree planting to solve these problems." Government opposition swiftly came, she said, "Because we had organized and challenged the mismanagement of the environment." No! The regime of Daniel arap Moi was responding to a challenge of its authority. Power was most important to the Moi government. If Maathai had not, using the momentum of her Green Belt Movement, contributed to civil disobedience it seems unlikely that she would have caught Nairobi's attention. Her third answer: "When people are educated to the links between environment and government, they can improve both." Again: what begot what?

Maathai says for her fourth answer that "Without a government that is respectful of people's rights, the environment will gradually be destroyed by privatization of public lands," and this is where we can see how environmentalism has, for Maathai, displaced polity founded on government by consent and self-determination. Kenya withered under government kleptocracy, not plutocracy, Moi's legacy being a deep-rooted corruption that today challenges Kenya's liberal Kenyan African National Union. Private property in a capitalist system encourages cultivation, and public appeals from a civil society insure national stewardship. Maathai's "privatization" was jobbery.

In her fifth answer Maathai posits that "If we manage resources more responsibly and share them more equitably, many conflicts over them will be reduced." For a third time, she misses the antecedent. In terms of land claims it is only incursions on sovereign boundaries that stir modern democracies to arms (see the Mexican and Falklands Wars) while domestic contestations, however grim, are resolved civilly (see Oregon's Klamath Basin).

Maathai's sixth answer betrays an unfamiliarity with Kenya's new system. Yes, destitute regions may require Nairobi's direct investment and constitution but to suppose that "People need opportunities and resources in the places they live," well, that is to effect a central planning that — even in the name of assurance — does great harm. Free markets are not floral arrangements: employment will come from wherever the market requires it.

Maathai concludes with hopes for the future of Kenya's youth, that "They can achieve something worthwhile." Certainly they can but with more difficulty should they continue to receive guidance like this. Elsewhere in National Geographic's September issue, the obligatory article on AIDS is bowdlerized. No, by this time very few people are ignorant of how the virus is transmitted; but for all the statistics and narratives offered for Africa's (and Kenya's) victims, an assessment of how a disease communicated by indiscriminate behavior is absent. How, then, can the problem be solved if its anatomy goes partly unexamined?

Well, we know what Wangari Maathai thinks of AIDS, and National Geographic has published to what she attributes Kenya's awakening. It is all right for someone to take part in great deeds they don't understand so long as no one simply assumes they do, and does not try to conflate circumscribed expertise with knowledge of everything else. Kenyans have a nation to bring up, and do not need muddled advice.