This is a continuation of my mention of Goethe yesterday.

In 1984 or 1985 my aunt was dating illustrator John Jude Palencar (now my uncle). She had purchased (or he had given her) several books to which he had contributed, and every time my family visited her apartment I'd run straight to the books, curl up in a corner and feast my eyes on the surreal, macabre and fiendishly enjoyable work of Uncle John and his colleagues. One collaboration was for a Time-Life Books series celebrating folk tales, mythology and fantasy, called the Enchanted World Series. In the first book, Wizards and Witches, Uncle John offered rich, finely brushed and deep-shadowed acrylic paintings of Manannan Mac Lir and "the Black School" which were, naturally, favorites. But I was always more greatly drawn to the pages retelling of the Damnation of Faust. Loosely based on the Goethe play, the book set its story to four watercolor paintings by Irish stained glass artist and illustrator Harry Clarke from a 1925 edition of Goethe's Faust — a copy of which sits in the Cleveland Public Library's special archives, one that I've held in my hands. Clarke is not well known at all in the art world, but those who are familiar with him will immediately recognize his stylized, elfin human forms and penchant for visceral, almost biomechanical ornament that predated H.R. Giger by four decades. He was sought out to illustrate stories calling for elegant, unnerving images and succeeded wholly with his paintings and ink drawings in Faust.

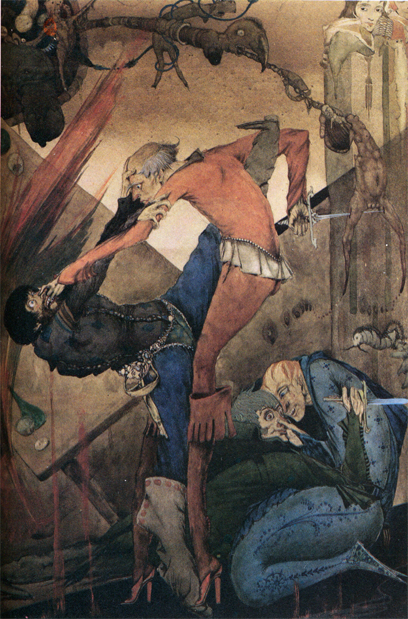

One of the four watercolors is of "Auerbach's Cellar in Leipzig," where Mephistopheles tricks four drunkards into beating one another senseless. Clarke was able to capture the bewildering violence as Goethe intended it, I think: grim and gory but lurid, almost salacious in its devilish manipulation. "The demon smiled" with Faust in a safe corner, goes the book, while "young men fought like beasts." Watching flesh controlled by evil is not a pretty sight, and I see no distinction between the hysteria of this tragic scene and the short, savage, meaningless lives of the terrorists and thugs fighting our men now.

Faust. I do not imagine I know aught that's right; I do not imagine I could teach what might Convert and improve humanity. Nor have I gold or things of worth, Or honours, splendours of the earth. No dog could live thus any more!

ON CLARKE: Keep in mind that I was six and seven when first exposed to this stuff. The macabre made quite an impression on me — a good one, I think, as I took to a sort of figurative abstraction in my own art and in some understandings of the world as early as junior high. Funnily enough, I brought the book Wizards and Witches into a portrait class in college. Our professor, Jerome Witkin, asked us to describe a stirring portrait and explain its significance. "Auerbach's Cellar" isn't exactly a portrait but it was a powerful study of the heart, and had kept me stirred for fifteen years — so its selection was a natural one. Said Witkin, whose work is equally otherworldly (link not entirely work-safe), "uh-huh. This explains a lot."